I can't afford to buy the art I would like to have hanging on my wall. I can, of course buy prints of it, but it's not quite the same, is it? However, I indulge my love of art in a medium which is a little closer to some artists' intentions, that is through book illustrations. As discussed in my previous post about lovely Percy Bulcock, there are oodles of wonderful artists who illustrated poetry, and today's post is about another one of them, the redoubtable Olive Allen...

|

| The Lovely Olive Allen... |

Olive was born in Lancashire in the autumn of 1879. Her father, George Lupton Allen, was a Wesleyan minister, who had married Mary Jane Pethybridge in the late 1860s. Little Olive was the youngest of the brood, which included three sisters and three brothers. While her father was preaching (whenever I think of that I picture a scene from Cold Comfort Farm, where Amos goes preaching out the back of a Ford van to the Quivering Brethren), the family moved around, but finally, after George's retirement, the family settled back in Mary's native Cornwall. It was there that the family lived in Denheved School in Launceston, in a house called North Hall. There appears to be a North Hall Court in Launceston still, in Denheved Road, so I'm guessing that is the same building, split into smaller residences. The mother was the Principal of the girls' school and Olive's sister Margaret was a teacher.

|

| From Tanglewood Tales (1908) |

Olive was rather keen on art from an early age and wrote to James Whistler for an autograph for her scrapbook (which he duly supplied). According to sources on the internet, her scrapbook with its many autographs, pictures and poems is still in the family. How marvellous!

|

| Pandora (1920s) |

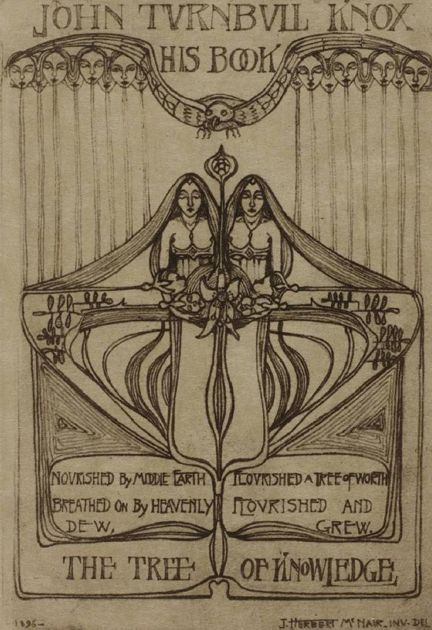

Olive didn't fancy going into what seems to have amounted to the family business of teaching or preaching, so took herself off to art school. First of all she went back up north, to Liverpool School of Art and Architecture, where she was taught by James Herbert McNair and his magnificent moustache...

|

| Well, hello there, James Herbert McNair |

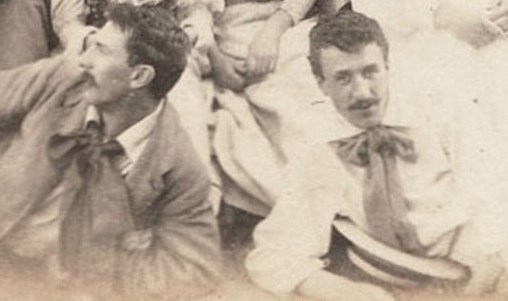

McNair had been best friends with Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who I must admit I mistook him for when I first saw the picture, but just to prove they were separate people, here's a picture of them together...

|

| McNair is definitely the one with the moustache and the floppy bow... |

From there, Olive travelled back down south, studying first at Lambeth and then at the Slade School of Art, where she was taught by the formidable Henry Tonks. Olive was just one of the countless famous artist who had all fallen under Tonks' 'hooded eye' (according to another pupil, Paul Nash). I love Nash's descriptions of Tonks, who sounds terrifying, and so sarcastic and derisive that the novelist F M Mayor's sister quit before she could complete her course. Olive very sensibly didn't quit but apparently drew a rude cartoon of Tonks, which is always the best plan for dealing with people.

Olive was at the Slade until 1903, but started to work as an illustrator from 1901 in magazines, children's books and annuals. In the 1901 census, she is staying down with her sister Margaret, the teacher in Launceston, probably for the Easter holidays. Olive's books are available to buy second hand and my own interest in Olive came when I bought her illustrated Sons of Innocence by William Blake, published in 1906. The publisher was TC&EC Jack of London and Edinburgh, for whom Olive illustrated many projects. How could you not fall in love with images like these...

|

| Frontispiece of Songs of Innocence |

That last one is obviously a social distancing nightmare and I shouldn't have to remind you all that no-one should be encouraging little lambs to lick anyone's white neck right now.

Anyway, Olive returned back to the school in Cornwall, now managed by her sister while she made a living as a 'painter' (as she is listed in the 1911 census). Somehow, around this time, she met John Biller. As her work was mostly in London, it is most likely she met him in the big city rather than the west country because Mr Biller had a rather more adventurous life than a private school in Cornwall. He had been born in 1877 in London, the son of a prosperous wine merchant. When John was 10, his father had died, leaving his mother with four young children to care for. A hint of what lay ahead is in the last census that John's father appears in - a guest in their house is John's uncle who had emigrated to America. As soon as he was old enough to do so, John emigrated to Canada, around the same time as Olive was at art school, but he obviously made frequent visits back to England, where he met and married Olive in 1912. Olive returned with him to Canada to start their new life. Their son John Trebarfoot Biller was born on Valentine's Day in 1914. However, their happiness was not to be long-lived.

|

| Simple Susan (1925) |

The First World War being what it was, John died. On his 'Circumstances of Casualty' card it records his death as being in Sanctuary Wood in Ypres in June 1916. He had been reported missing in action but his comrades made statements to the effect that John had been on duty, when the enemy entered the trench. Despite the attack being repelled, John was killed by a shell. Not to put too finer point on it, shells falling and being missing often do amount to the same thing. War is just horrible.

|

| Tanglewood Tales (1908) |

Olive returned to Canada with her children and moved the family to James Island in British Columbia. In the 1921 census, Olive is not listed as an artist but as a stenographer, hinting that she broadened her work to support her young family as a war widow. However, a move to Victoria in the late 1920s saw her flourish again as an artist in the burgeoning Arts and Crafts scene. She worked until her death in October 1957 and has subsequently become known as a Canadian artist and illustrator. It is a joy to find that the books she illustrated are available to buy via sites such as Abebooks (who own me, the amount of time and effort I spend on their site) and so you too can own a little piece of heaven, thanks to Olive.

There is a wonderful resource on Olive here and it is good to know that much useful research is being done into Olive's life so she, unlike Percy Bulcock, will not slip into anonymity.