I warn you now, this is a very cross post. As you might have heard, I am currently researching and writing a biography on Ethel Warwick, star of this post, but while researching her, I ended up falling in love with Lewis Waller...

Lawks! Actually, I prefer this one...

If I ever write a biography of my new boyfriend Lewis, this will be the front cover image as he's so dreamy. Anyway, I digress. The beautiful Mr Waller was actually Ethel's father-in-law, therefore of great interest to me for that reason - The Swanage Times and Directory in September 1928 reported that Ethel visited the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery in Bournemouth to see the painting they have of Lewis Waller by John Collier...

|

| Lewis Waller as Monsieur Beaucaire (1903) John Collier |

That gorgeous (and enormous) portrait of Waller can be seen today still displayed in the gallery and it is a stunning sight indeed. Anyway, the reason for this post was that whilst researching Ethel Warwick, with an eye for images to use in a book, I bought a collection of postcards. It was a massive bundle of over 100 images in a tatty album and it cost me £20. Now, I thought that if I used a few of them, it would be cheaper than attempting to find individual ones. I also counted on finding an image of Waller's erstwhile son Edmund, Ethel's first husband, who was also an actor, and Waller's wife, Florence West, who was an actress and company manager, who gave Ethel work (hence how she met Edmund Waller). However, that wasn't all I found. I got sucked into the world of Waller-Adoration, a much maligned fan club and an astonishingly criminal vicar. Brace yourself...

|

| Lewis Waller as Robin Hood (c.1904) |

Look at the little mice! Adorable.

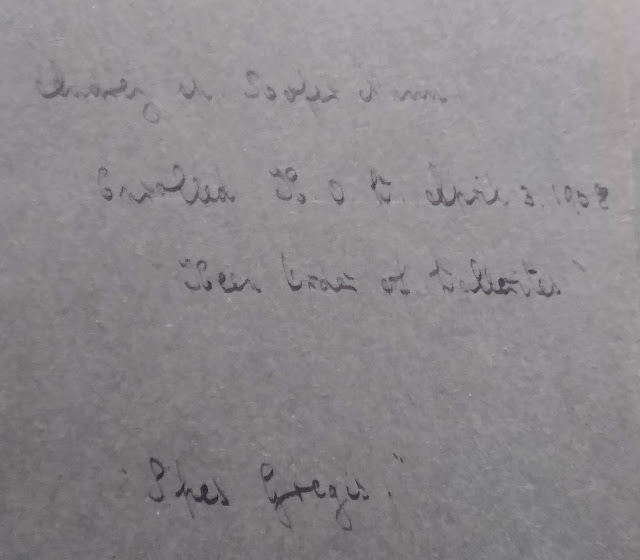

My story begins with the photo album I acquired. Battered and rather falling apart, it appeared to be the collection of one person, who had inscribed the front endpapers of the album and some of the photographs. Although it was faded, I could just about make out the inscription...

The inscription reads -

Audrey M Roper Nunn

Enrolled KOW April 3, 1908

Keen Order of Wallerites

Spes Gregis

As you can imagine, I was keen to find out a bit about Audrey, but I also wanted to know what the KOW were and given that she had collected 100 postcards, I wanted to know Audrey's story with Lewis Waller. The 'Spes Gregis' comment was also interesting - why was Lewis the 'hope of the flock'? The answers to these questions not only told me a lot about the devotion of women to a talented man, the fate women suffer in the newspaper and why Audrey needed Lewis Waller more than he could ever have known.

|

| Lewis Waller and Madge Titherage in King Henry V (1908) |

Lewis Waller (1860-1915) was one of Victorian and Edwardian Britain's most popular stage actors. Handsome, romantic and accessible, it was unsurprising that Mr Waller would attract a devoted female following who religiously attended his performances in order to worship. By 1907, he was arguably the biggest star of the stage, starring in and managing some of the most successful performances in London and beyond, touring all over Britain and the world. For his 47th birthday in November of that year, he suddenly received 30 telegrams wishing him well, all signed 'KOW' which utterly puzzled him. Little did he know that Miss Amy Skelton of Streatham Common had formed a group with other likeminded men and women (mainly women, let's be honest) to meet every Monday to discuss how awesome Lewis Waller was. They were the Keen Order of Wallerites, or the KOW and they formed the first ever celebrity fan club in existence.

|

| Lewis Waller as Brutus (1900) Edward Onslow Ford |

Being a member of the KOW had some pretty strict rules. As Miss Skelton stated in the

Daily Mirror, 'As you can see, we are not silly, giggling school-girls ... we are all old enough to know good acting when we see it, and it is the acting of Mr Waller that we admire... it is the actor rather than the man who holds us together.' Miss Skelton was interviewed in April 1908 about the KOW, interestingly just as Audrey Roper-Nunn joined their ranks and I wonder if she had read the report in the

Daily Mirror. By that point, the KOW had been in existence for 6 months and generally not known to those who were not regular attendees of Waller's performances. The group booked seats for the first and last nights of the shows but otherwise took their chances at the pit door in the queue, often waiting for up to 4 hours for a seat. Miss Skelton was a practiced hand at this, admitting she had waited in a queue for 12 hours to see Sir Henry Irving and would do the same for Waller. Many of the KOWs had seen Waller's recent plays up to 50 times, which gives you an idea of the economic status of the women (and men) involved.

|

| Lewis Waller in Brigadier Gerard (1906) |

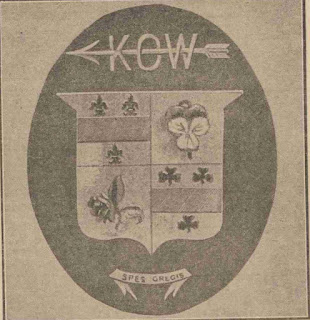

The Daily Mirror article was remarkably in-depth and respectful of the group and Miss Skelton was very keen to emphasise that the group were just interested in the performances rather than being groupies. There was no 'hugging' of the stage door allowed as it was seen as bad form and would annoy Mr Waller. Waller's brother Guy had noticed some of the women who had been frequent attendees at his brother's performances and had been asked for 2 signed photographs of Waller but otherwise had not been bothered by them. Lewis Waller himself, when informed of the group was gratified that his acting pleased them, no doubt delighted he was guaranteed seat sales. The only way the members of the KOW could be identified was the badge they wore, created by Miss Skelton from designs by her artist brother...

The badge was formed on the back of a photograph of Waller. The reverse side featured a quartered shield, with a rose, a pansy, a fleur-de-lis and a shamrock in the 4 parts. The pansy was Waller's favourite flower, and the rose, lily and shamrock represented the 3 plays the KOW most admired, Monsieur Beauclaire, Henry V and Clancarty. The arrow across the top was for his performance in Robin Hood. Spes Gregis, written across the bottom, refers to 'the hope of the flock' and how Waller was seen by his followers. Wearing the badge, which was coloured mauve and green resulted in the ladies being mistaken for suffragettes. Miss Skelton revealed that simply by turning the pin over to reveal Waller's portrait it enabled people to 'understand that we are women of sense and not- (she shrugged her shoulders)'. I wonder if Amy Skelton knew how the suffragettes were treated in the newspapers and therefore wished to distance what they considered quite a harmless fan club from potential ridicule. Well, Miss Skelton, I admire your optimism but I think we all know what's coming for any woman who says anything in public, especially as the Daily Mirror had been kind enough to print her address in the piece...

|

| Lewis Waller in The White Man (c.1908) |

Less than a week later, the Daily Mirror was back for a follow-up interview and the tone had definitely changed from merely reporting something of interest to mocking. Miss Skelton was now described as the 'Grand High Mistress of the Order' and the piece reported on the KOW presence at the 100th performance of The White Man. Miss Skelton and her friend were seeing the play for the 20th time and 'took up strong positions at the pit door at noon' in order to get tickets. It was reported that the KOW friends had had lunch together in the line, as the report said 'on the pavement, frugally'. In the past week, Miss Skelton reported she had received hundreds of letters and telegrams to her house as a result of the previous article. Some had been very abusive and one weekly illustrated paper had requested a photograph of the chief members of the KOW and a photo of Lewis Waller surrounded by his adoring women, to which Miss Skelton had replied 'certainly not!' Despite the KOW having some men as members, 6 in a membership of 55, it is the women who entirely get the brunt of the ensuing commentary. We think that women getting social media abuse is a modern phenomenon, but how comforting to know that women throughout history have been taken to task for existing in public. How dare they!

A day later, The Daily Mirror ran a photograph apparently showing the KOW waiting at the Lyric Theatre, incorrectly identifying them as waiting to see Waller. As reported in their own newspaper, the KOW queued for tickets but did not allow any loitering or bothering of the actors. Also, Miss Skelton had pointed out there were not formal meetings, they met in the queue or occasionally went out to tea. It had taken exactly a week for the group to go from enthusiastic theatre goers to groupies who lie in wait for unsuspecting actors. The use of phrases like 'strong position' de-feminises these mainly unmarried women and gives a very particular impression of the members.

|

| Anti-Suffrage postcard (c.1910s) emphasising strength of unloved women |

The same week, Punch magazine congratulated the Daily Mirror for 'unearthing' the KOW because, as they reported, 'if these suburban theatrical cults extend we shall expect to see other symbolic adornments on feminine bosoms in the various pit crowds.' On April 11, nine days after the initial article, Amy Skelton disbanded the KOW under increasing mockery and abuse which continued even in the article about it. Miss Skelton had recalled all the badges she had made, although some members refused to send them back. An unnamed (and I suspect, fictional) member was approached for comment which ran as follows - 'we are devoted to Mr Lewis Waller - the actor, mind you, not the man - and the members attend on first nights and other occasions and take every possible advantage of applauding him. We think he is just perfect - the actor, of course, not the man.'

The repetition of Miss Skelton's original assertion that they were interested in the actor, not the man is used here in mocking, patently calling out the women for lusting after Waller. Also interesting that the claims of disruption start here, that the women applauded Waller's every move and disturbed the play with their clapping and stamping. These claims are repeated in various books on theatre and reading Amy Skelton's account of their modest fanaticism, it's hard to imagine these middle-class ladies of really letting themselves go with wild abandon in the theatre. However, these claims affected how others spoke of Waller and the fact he had such a following might have meant he was not taken seriously as an actor. However, I would argue his good looks and obvious popularity bred jealously. If you are pretty and popular, you obviously can't be legitimately good at your job, apparently.

|

| Postcard from Audrey Roper Nunn's collection with the below written on the back |

|

| 'Waller, you darling! Why do you wear striped cuffs?' |

So, the KOW was disbanded in 1908, therefore the newspapers would have forgotten all about them, right? Of course not, because much like some sort of mythical creature, the KOW refused to die! Women were still allowed to leave the house and appreciate things and so the newspapers were on hand to ridicule them.

The Bystander magazine reported on 22 April that Lewis Waller had purchased a Rudge-Whitworth bicycle in order to escape the fanatical grasp of the KOW. The fact that Rudge-Whitworth had famous clients already, such as Princess Victoria, and that cycling was very fashionable, they had probably given him the bike in order to claim him for the brand, but that is not the point. He was obviously going to use the bike to avoid his fans. Let's hope the lady in the above advert isn't a KOW...

|

| Lewis Waller and Valli Valli (so good they named her twice) in The Duke's Motto |

In September of 1908, during the run of The Duke's Motto, The Bystander reported how it was 'a feast for Wallerites' and the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News commented that the performance had received an 'enthusiastic Wallerite response'. There was even a report of a KOW wedding between Augustus Camplin Smith and Janet Northam in 1909. That means there are only 5 KOW men left on the market, ladies! However, the wording is somewhat unclear - do we assume they are both members, hence the KOW wedding headline, or is it just Janet, as the Daily Mirror refers to the KOW as 'lady admirers'. Part of me suspects that it might just be Janet who was a KOW and the news piece is because one of the appalling lust-fuelled spinsters plaguing Mr Waller has managed to get married, look! I might be extremely pessimistic in my view of newspapers but I suspect that is the case.

Oddly, despite the disbanding of the KOW in 1908, comments in the newspapers continued, increasingly at Waller's expense. Waller was a handsome actor who played very physical, commercial parts - The Civil and Military Gazette in October 1908 commented of his performance that 'the whole piece is a festival of Waller and swordplay in which the acting of Miss Sybil Carlisle etc goes almost unnoticed.' Sorry Sybil, you just aren't as exciting as Lewis Waller and his sword.

|

| Lewis Waller in Bardeleys the Magnificent (1911) |

Having the KOW to blame for when a play was not successful must have actually been a bonus. The Bystander reported that the Wallerites enthusiastically embraced Bardeleys the Magnificent but had not liked the more serious pieces or the contemporary pieces Waller had put on over the year. His performance as the villain in Butterfly on the Wheel, a divorce drama, in the April of 1911 had not gone down well with audiences who could not believe him as a villain (although probably might believe they would commit adultery with him). 1911 proved to be a very trying year for KOWs (if they even still existed as a group, which is doubtful) as the Daily Mirror reported that Airmen were ousting actors as the new heores. The opening of a flying ground at Hendon had seen groups of women gather at the gates in order to see their new 'favourite idols', the airmen. The women were reported as being 'well to do and socially well known' which is very reminiscent of how Amy Skelton and her crew were seen, and in the article it said that several of the women were recognised as KOW - 'Judging by the postbags of the various 'airpilots' at Hendon, it seems that a good many KOWs are now worshipping at the shrine of the airmen.'

|

| Rachel Ferguson (1892-1957) |

A final nail in the coffin of the KOW came in 1923, years after Lewis Waller's premature death in 1914. The author Rachel Ferguson reported that she was proud never to have been a KOW and 'gorge rose (and rises yet) at the exhibition women of thirty and over made of themselves about Wednesday and Saturday Gods.' There is so much wrong with the sentiment that Rachel Ferguson expresses that I'm not sure where to start. Women of thirty and over are allowed to lust after people, thank you very much. Well done on doing the work of the patriarchy, Rachel, which is a puzzling stance for someone who is now seen as a feminist hero. This generalised, cheap-shot journalism made me angry because of the story of the KOW I got to know. Say hello to Audrey Roper Nunn...

|

| Lewis Waller, from Audrey's collection |

|

| Written on the reverse - 'You are a scowling boy here!' |

When I received Audrey's collection of Waller postcards, I didn't intend to look into her life, but you know me, of course I did. I really only expected to find a middle-class lass who enjoyed going to the theatre and in a way, that's what she was. As I said above, I suspect she read the article in the newspaper and became a KOW, either officially or self-diagnosed (both are valid), allowing her long-held adoration of Mr Waller to form the collection of cards. On the reverse of a lot of them she records when she attends the relevant performances, but my favourite card, above, has the phrase 'you are a scowling boy here!' on it. It is now common in the Walker household to be referred to as 'my scowling boy!' as a term of affection. Audrey was born in 1888 in Sutton in Cambridgeshire. Her father, Douglas, was the son of a very well-regarded JP and was in the church, ordained as a deacon in 1882 and a priest in 1883, so the family moved around a lot. I don't have a photograph of Audrey, which is a great pity. However, I do have a few of her father. This is not a good sign, I warn you now...

By 1900, the Reverent Roper Nunn was bankrupt and had to auction off his belongings to pay his creditors. In 1903, he was 'defrocked' for theft, but continued to find work as a priest and continued to steal, getting caught and charged in 1909. It had been noticed that at each of the churches he had worked (and those in the vicinity) money and belongings would go missing. Mr Justice Lawrence who tried his case at the Essex Assizes said that he had 'lived a life of disgrace, and it was impossible to imagine a worst offence.' Douglas went to prison for 3 years. He had been encouraged to reform his life but when he was released, he started stealing once more, getting another year in prison in 1914 and another in 1918.

Now, I'm not one to gossip, but there was also an incident in 1897, when the Reverend ran over and killed 75 year old Amos Cornish, while on a tricycle (Douglas, not Amos). It had all happened one night after Roper Nunn had been visiting his brother, and he had managed to plough down the elderly gentleman on a straight piece of road - comment was made that the victim must have seen the tricycle coming so should have moved, rather than the vicar shouldn't have run over someone at considerable speed. Given the events of the following two decades, I wonder if there was more to it, not that I am accusing Roper Nunn of being homicidal, but as he often stole from neighbouring parishes, possibly Cornish saw him and in chasing after the witness, Roper Nunn accidentally ran him over? Probably it's all a coincidence but I am definitely having that in a book in the future. Back to Audrey...

|

| Lewis Waller (c.1890s) from Audrey's collection |

In amongst her father's criminal activities, Audrey was finding her way in the world. As the oldest of the five Roper Nunn children (four of whom survived infancy), she would have witnessed the family's downfall very clearly. From the rather well-to-do young lady from a very good family, by 1911, she was working as a servant for the Tebbitt family in Hampstead while her mother and her three siblings lived in a small house in Brentford in Essex. I wondered if her move to London for work made it easier to visit the theatre or whether it was financially out of the question? In 1923, Audrey enrolled in training to become a nurse and lived her life that way, dying in Brentwood in Essex in 1972, having never married. I think it is no coincidence that the majority of her collection comes from the years between her father's defrocking and his imprisonments. Her notes written on the back on the cards not only show that she regularly attended his performances but felt a connection to this strong, handsome hero, who was capable, honest and reliable. From her late teens to her early twenties, Audrey followed Waller, collecting the cards, swapping with friends who collect other actors and receiving them from her brother Kenneth. I hope it made her happy because I can't imagine her homelife was easy.

Bearing Audrey in mind, reading how the KOW were talked about in newspapers and in books makes me angry. In Hesketh Pearson's 1921 book Modern Men and Mummers he writes that Waller didn't like 'the clique of maiden ladies who made poor Waller look ridiculous in and out of season' quoting him as allegedly saying 'will no one rid me of these turbulent priestesses?' Furthermore in his memoirs of 1938, Pearson reports how Waller was known for his 'hoards of women' who formed the KOW. I would hardly call 49 (there were 6 men, remember) a hoard, and the tales of their misbehaviour seem out of character from Amy Skelton's very dignified interview. Other stories circulated, including one quoted in Ben Iden Payne's A Life in a Wooden O: Memoirs of a Theatre (1977) where Herbert Beerbohm Tree recalled a woman shouting 'How dare he!' at an actor who had wronged Lewis Waller's character in a play. There is nothing to say that the lady in question (if it even happened) was a KOW but it was assumed she was and therefore one of the hoard of worshipping old maids.

In varying publications the KOW are described as a band, an army, a hoard of young (and not so young) women whose adoration of Waller makes both parties ridiculous, however wasn't that the point of the parts he played? Waller admitted he adored Shakespeare the most, so in playing the heroes was not the point of the performance to admire him? In the popular romantic parts he was also famous for, the fact that he was so commercially successful by being the square-jawed, sonorous-voiced manly man meant that they had long runs of performances with the KOW queuing for tickets. There is no contemporary account of the KOW disrupting performances other than applauding loudly for Waller and I have no doubt if they had done any of the other things they are later accused off, like stamping, shouting and generally being uncontrollable, it would have been in the Daily Mirror. Stories breed stories and narratives form to suit the story tellers. In the smug memoirs of the 1920s and beyond, no-one talks about the hate mail received by Miss Skelton because she said she enjoyed seeing Lewis Waller perform. A few actors comment that Waller was a great performer but could be a little overwhelming to the others on stage with him; that must have been galling if you are a co-star, especially if Waller gets rapturous applause for squashing (even inadvertently) your part and career. I read jealousy in accounts of Waller's fan club, the first of its kind and a definite forerunner for film star adoration of the 1920s. Yet again, a talented, popular but possibly flawed man is ridiculed using women (yes, I'm bringing it back to Rossetti and Fanny again, as I always do) - How can he be so great if those ridiculous women love him? And if he is ridiculous, what does that say about the women who love him?

What seems to be mocked here is female desire, especially in women over thirty and unmarried. It is no coincidence that the mocking of the KOW happens during the years of suffragette action. The power, desires and actions of educated, middle-class unmarried women terrified the establishment because what is it they want if not to be married? These women do not know their place! I don't know why Amy Skelton formed the KOW, or her life after disbanding the group, but it is easy to see the pleasure Audrey Roper Nunn got from her collection of postcards, during a difficult period of her life. The mocking of Amy and Audrey and the other women who dared to enjoy something designed for their enjoyment is breath-taking. The fact that the alleged misbehaviour of a few theatre goers is entirely blamed on the KOW, that they become the 'turbulent priestesses' who ruin the life of the very man who they admire is the newspapers once more performing their magic trick of ridiculing successful men by demonising women. The Daily Mirror's astonishing manipulation of the story, the way Amy Skelton was mocked and the general dog-pile of abuse for the next decade and beyond is a sobering lesson in how our society and especially our media can be frighteningly misogynistic.

The fact that we still trust newspapers proves that we are either ridiculously optimistic or idiots as they have repeated shown they cannot be trusted with the lives of women. As always, my message is to dig deeper, question everything and if you are a woman over thirty, I hope you have a scowling boy (or girl) who makes you happy.

.png)