I have a rather dubious confession to make about my research - I absolutely love divorce papers. I'm not sure what that says about me, very likely nothing good, but you learn an awful lot about people from the accounts in the supporting statements submitted with the various decrees. I know of one well-respected Pre-Raphaelite painter who punched his wife in the face with a book, something I've never read about him in any biography. Sometimes it's graphically awful and you are delighted that you are reading this in a divorce document rather than a newspaper report after their murder (sorry, Dolly Henry). Anyway, all this confession is in way of explaining how I met Alice Havers...

|

| Rush Cutters (1887) |

Alice Mary Celestine Havers was born into a very well-to-do family in May of 1850. The Havers lived at Thelton Hall in Norfolk, which had been built by Thomas Havers in around 1592 with a chapel which no doubt houses generations of Havers. Alice's Dad, yet another Thomas (1810-1870) decided the Norfolk life was not for him and so moved to the Falkland Islands (which is a bit of an overreaction in my opinion) in 1854, with her older siblings, mother, Ellen, a nurse and governess Mary Coppinger. Alice's childhood was spent growing up in the Falklands, which is fascinating to people of my vintage who really only know a few (mainly war-related) things about the Falklands. There is a very good, Falklands-centric page on Alice here. Sadly, Ellen died not long after they arrived in the Falklands. Thomas then promptly married the governess. Moving on.

|

| They Homeward Wend Their Weary Way (1875) |

When Thomas left his work with the Falkland Island Company, he took his family over to Uraguay, where he died in 1870, when Alice was 20. She was finally free to have her own life and returned with some of her siblings to England. Her sister Dorothy became the writer Dorothy Boulger, after marrying in 1879 (presumably publishing in her maiden name from her first book in 1871 until then). Alice attended the art school in South Kensington and began painting and exhibiting her works. She became quickly known for her small and delicate works on slightly melancholic or rural scenes. The Gentlewoman magazine commented on her work after her death as being 'graceful, delicate, almost ethereal...She never painted anything large or very ambitious in design or colouring', but this was because each painting was a treasure of beauty from her heart, according to the gushing memorial. It is easy to see what they meant when looking at pleasing images such as Blanchisseuses: What, No Soap? (1880)...

|

| Blanchisseuses: What, No Soap? (1880) |

She also illustrated many books, including her sister's, becoming known for her expressive line drawings...

|

| 'Bobby, My Boy' from Bumblebee Bogo's Budget (1887) |

|

| 'Nautilus' from Bumblebee Bogo's Budget (1887) |

She married fellow artist Frederick Morgan in April of 1872 at St George's in Bloomsbury, falling pregnant almost immediately. The couple's son, Valentine, was born the following February. In most accounts, Valentine Havers (yes, he took his mother's name when he became a professional artist) was born on 13th February, rather than the assumed 14th, but in the divorce papers of Alice and Frederick (sorry, spoiler alert, but we all knew it was coming), his birthday is listed as 14th, which makes more sense, given his name. The little family lived at 5 Clyde Street in South Kensington to start with (Clyde Street has since been renamed Redcliffe Place, part of Redcliffe Gardens, by Redcliffe Road, making them neighbours of Alexa Wilding. It's a small world etc etc) and were joined in 1875 by daughter Lilian, moving round the corner into Cathcart Road.

|

| Frederick Morgan |

Although he possessed a great big moustache, Frederick Morgan does not strike me as a happy or particularly nice man. In the divorce proceedings of 1889, Alice is very specific about how atrocious their marriage had been. Trouble is recorded as starting even before Lilian was born, with the first affair coming the year after Valentine was born. In 1876, Frederick committed adultery in Dieppe (I'm not sure if that's a comment on Dieppe as I have never been there and possibly for the good of my marriage, I shouldn't). In 1878, the Morgan's housemaid, an aptly named lass called Hetty Screwby, was found sitting on Frederick's lap in their studio, and his retort was that Alice should not have employed such an attractive maid. Frederick's affair with Rose Kerrison, in Park Walk, Chelsea, resulted in him catching an STD, but on top of these many affairs, Alice claimed that Frederick was often violent towards her. In the divorce paperwork, Frederick denied all of it, claiming that any time he struck Alice was entirely in self defence, but undermining this was the presence on more than one occasion of Dorothy, who backed up her sister's stories of mistreatment. On one occasion, Frederick pulled Alice off a chair, on another he forced her onto the floor to make her apologise, then dragged her round the room by her arms after a disagreement over seating at that evening's dinner party. Alice was so badly injured that Dorothy had to take her place at the event.

After all that appallingness, possibly it is unsurprising to learn that alongside all the pastoral loveliness, Alice had quite a talent for an unhappy picture, such as this one...

|

| End of her Journey (1875) |

I actually wrote a post on this painting as part of Sobvent back in 2019. It was an absolute hit when it was shown in 1877 in Liverpool with crowds gathering around it in the galleries. Newspapers rhapsodised about the wistful little child clinging to the dead mother, and the callous indifference of the onlookers. The Yorkshire Post debates whether the woman is actually a tramp, 'unknown and uncared for' who has been found by the workers on their way to the fields. The Manchester Courier refers to the woman as a 'returning wanderer', suggesting the woman has come home to die. The various, sometimes contradictory readings of pieces of narrative art is why I love this sort of picture.

|

| Trouble (The Sick Child) (1882) |

When this painting was exhibited with the Society of Lady Artists in 1885, it was praised in the way she 'treats the domestic sorrows of humble life with touching tenderness of sentiment.' I think there is no coincidence that the image looks like one of her well-known and loved images of another mother...

|

'But Mary Kept All These Things And Pondered Them In Her Heart' (1888) |

Interestingly, although this was a very popular painting with the general public, there were some criticisms, including the appearance of the Virgin Mother, which was outrageously shocking, apparently. According to the Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail (Clarion of Truth, no doubt), there was a lot to be questioned about these presumptuous lady artists:

'The girlish figure with her pretty thoughtful face, and soft brown hair falling about her shoulders, is certainly anything but the conventional Madonna, and you can enquire disapprovingly why the lady artist has thought proper to depart from the traditions of more than a thousand years. It surely, you will suggest, argues an unwise amount of presumption and besides, if the BVM is to be represented entirely according to the caprice of the painter, it leaves the field open to endless offence against good taste. Perhaps we might eventually find her attired in the latest novelty of nineteenth century fashion, or even represented with the features of some fashionable beauty. Eccentricity, you will crushingly conclude, is not the true offspring of original genius, but only its bastard imitation.'

Well, that's us told. Apparently it's disrespectful to show the Holy Mother with brown hair, but it's cool to refer to the Blessed Virgin Mary as BVM...

|

| Advertising card for The Gondoliers by Gilbert and Sullivan |

Alice also illustrated programmes for Gilbert and Sullivan operettas, providing the perfect blend of whimsy and playfulness that the works inspired. I particularly liked this card for The Gondoliers, which I appeared in (an amateur production) aged about 15. My costume was nowhere as nice as the lady above, although my kimono for The Mikado was gorgeous. I digress.

|

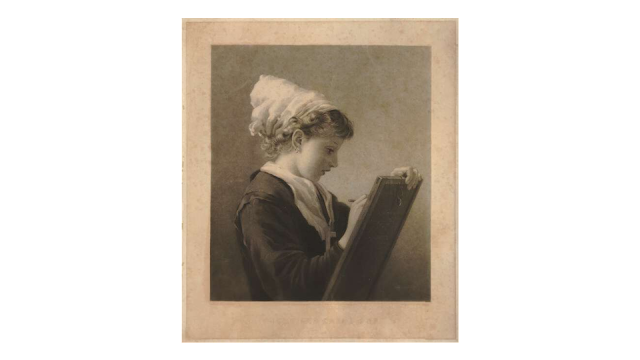

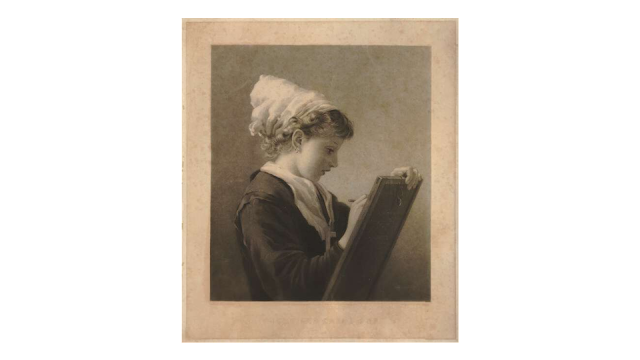

| Ought and Carry One (1874) |

When Alice exhibited Ought and Carry One at the Royal Academy in 1874, Queen Victoria bought it during the private view, as she was so charmed with the image of the school girl puzzled by a sum. It had already been purchased by someone else but apparently if the Queen wants the picture, there really is no arguing with that. I think the sentimental nature of many of Alice's pictures made them perfect subjects for prints and engravings that appeared in magazines, perfect for the walls of your own home. Her work, and that of many other artists including her husband, saw their narrative works become popular and loved by the sort of people who might not make it to the Royal Academy, but knew what paintings were popular. It is one of those circular discussions - are they popular because they are prints or do they become prints because they are popular? It certainly doesn't seem to be because they are critically acclaimed, but maybe the more commercially canny watched to see where the crowds gathered during public viewings and those were the pictures that were selected. It's a fascinating process, dictating taste.

|

| Fast Asleep (undated) |

Fred's affair with his model, Mary Reardon, lasted all of 1888 and involved them going to Shanklin, that well-known sin city. That appears to have been the final straw for Alice who packed up her children and went to Paris. Whilst there, she filed for divorce and returned to her studies in art under Benjamin Constant. By this point Valentine was 15, Lilian 13 and Reginald 7 so must have been aware of what was occurring in the family home. Alice's health was suffering and the divorce was drawn out over a year with Fred contesting the claims of cruelty and adultery. However, as the newspapers gleefully reported, Dorothy had been present in the house for the violence and Fred and his mistresses had not exactly been discreet so he didn't have a leg to stand on. The divorce was finally granted on 1st July 1890 with costs awarded to Alice. Alice and the children moved back to London, to St John's Wood where she rented a house with a studio, but the new life was not to last long. She had been suffering from neuralgia and medicating with morphia, injected straight into her forehead, spending her nights on the coach in her studio. On the morning of 25th August 1890, the maid found her insensible from an overdose, with the needle still clenched in her hand. On the table was a letter to her doctor, describing her symptoms as unbearable and requesting another course of treatment. She died the next day. The newspapers had a field day and I wonder if this was an escalation of the mild (by comparison) interest shown in Elizabeth Siddal's death, almost 30 years previously. There were some newspapers that made much of the fact that she was newly divorced, therefore miserable not to be married anymore. Some drew an interesting line between her status as a successful career woman and mental instability. Much of her obituaries concentrated on her (ex) husband, calling her Mrs Frederick Morgan, and her male ancestors, one of whom was Gentleman of the Horse to John, Duke of Norfolk at the Battle of Bosworth Field. In the Pall Mall Gazette, an obituary 'by One Who Knew Her' remarked how she was 'the best dressed woman in the room' at the last meeting of the Salon, 'her dress somehow always had both cachet and courage, and her slight, girlish figure enabled her to adopt with success combinations of colour that in greater mass would have looked audacious.' They went on to praise her 'little fame'. Charming. What was enduring was the popularity of Alice's art with mentions of her talent after her death, and reprints of her popular pieces, possibly even more popular with the tragedy attached.

|

| A Turkish Lady (undated) Val Havers |

As a sad postscript, Valentine followed in his mother's footsteps and also became an artist, using her surname, which I think is very telling. He also married and divorced, with Valentine taking after his father in his many affairs, including liaisons on the Isle of Wight. I have to start asking questions about what's in the water over there... The decree nisi was granted in October 1911 but Valentine died in the January 1912, a sad echo of his mother, again in his 40th year. Both Lilian and Reginald died before 1920, both shy of their 40th birthdays. That's a very specific family legacy.

Dear Kirsty

ReplyDeleteAnother lovely artist to be introduced to, who was treated badly by a man! I really like her Virgin Mary - she looks young and somewhat overwhelmed. 'What no soap...?' reminds me of Millais' Apple Blossom. I like her use of colour. Thank you for the introduction.

Best wishes

Ellie

Thank you for another informative and entertaining blog. I thoroughly enjoy your writing, whatever the subject. Never be ashamed of your interest in divorce papers. As a family historian of 30 plus years my long suffering family are entirely comfortable with the fact that I like nothing better than visiting graveyards and receiving death certificates as presents. My own particular obsession is with wills. We all have our vices.

ReplyDeleteWonderful to discover this! Fred Morgan was my great-grandfather, and I had no idea Alice was so talented. I will treasure these images!

ReplyDelete