Often when I am researching one person, I get sidetracked by another who crops up in their story. As you can imagine, this happens quite a lot for me and to be fair, is how I end up writing about such a lot of people but I also end up with random books, pieces of paper and promises to women artists that I will come back for them at some point. As you will remember from my post of Mrs Byam Shaw, I absolutely love her and her husband, which is how I ended up meeting Maud Tindal Atkinson...

|

| Roses: Still Life (undated) Maud Tindal Atkinson |

I do appreciate a subject with an interesting name which will make them easy to find in the records. My ability to find Fanny Cornforth when she was just being plain 'Sarah Hughes' was severely hampered by every third women in Wales being 'Sarah Hughes' as well. I must admit the Tindal Atkinson family are pretty easy to spot, and their wealth makes them even more visible. Maud Tindal Atkinson was the second daughter of Henry and Marion Amy Tindal Atkinson and was christened Amy Maud, named after her mother's middle name. Her elder sister Ethel was Ethel Marion - interestingly Henry (who was also a son of a Henry) named his only (surviving) son Edward Hale Tindal Atkinson, which raises some interesting questions, but there might have been another son destined for the name who did not survive. Maud's dad was a barrister and married Marion in 1873, with Ethel following in 1874, Maud in 1875, followed by 4 other siblings, ending with Doris, born in 1890. The family lived in Beckenham in Kent, and I admit I am servant-obsessed, but they had five of them in 1891, so the family was not doing at all badly, thank you very much.

Now, what irritates me about census returns is that there is very easy erasure of female-occupation and this is especially common when people are wealthy. Possibly there is some sort of correlation between the number of servants you have and the likelihood that your daughter will be able to admit that she has a job. Anyway, we have to wait until the 1911 census (all hail the 1911 census, my second favourite after the 1939 census) before Maud admits, aged 35, that she is an artist. For goodness sake. So, what had she been up to in the previous 35 years?

The Tindal Atkinson family were Dorset celebrities. When Grandad Henry Tindal Atkinson died in 1890, his glowing obituary in the Blandford Weekly News spoke of the loss of 'the fine old race of sergeants-at-law' and other accounts contained descriptions of his coffin and the fact that Wimbourne Minster gave a special peal of bells. Maud's father was one of around a dozen siblings all of whom were successful, the boys receiving university education and going into professions like law and civil engineering.

|

| Maud (c.1890s) |

Maud attended St Swithun's school (who have this page on her), then received her art education at the Art Department at King's College for Women, and was lucky enough to be taught by Byam Shaw. In 1906, one of Shaw's Royal Academy paintings was a life-size portrait of her entitled Maud, Daughter of His Honour Judge Tindal Atkinson...

|

| Maud, Daughter of His Honour Judge Tindal Atkinson (1906) John Byam Liston Shaw |

Obviously, framing her as the subject of a painting because she's someone's daughter jars now, but might be reflective that it was commissioned by her Dad and very much reminds me of the Georgian portraits of rich girls finding husbands. If that was Judge Tindal Atkinson's plan, he should have known that meeting Byam Shaw tends to confirm women in spinsterhood (just after Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale). I like to think it is because he's so great no other man can compete. Moving on. The commentary on the piece in Rex Vicat Cole's biography of Shaw is a tad gushy - ''...of a beautiful sitter, one of his students...Her natural charm, added to a gift for understanding what was in the artist's mind, as well as an admiration for his work, and sympathetic help, made her a valued friend and an ideal sitter.' He also lists her other modelling jobs as The Caged Bird and The New Voice, the latter being a very interesting and telling reflection of the couples' friendship. Firstly, The Caged Bird...

|

| The Caged Bird (1907) John Byam Liston Shaw |

Maud is playing the part of a young governess, 'caged' by her wealthy employers who are visible in the topiary gardens, which were painted in Condover Hall in Shropshire. In a little act of rebellion, she has released the songbird from its cage because at least one of them gets to be free. It is unclear from her complex expression if she intended to do it, if she regrets it because she will get in trouble or if she envies the bird because she will never know that freedom, but it is wistfully beautiful. It is also an interesting piece by a man who was wealthy enough to have servants, of a woman who likewise had staff and the painting would no doubt be on show and on sale to people who had servants (although it seems to have remained in the Byam Shaw family until it was sold after Glen Byam Shaw's death). I admit, he's talking to the people who should have been made aware that their staff could be unhappy and the plight of the governess, positioned in a sort of no-man's land between family and servant, was a popular subject for the Victorians. Now onto The New Voice...

|

| The New Voice (1909) John Byam Liston Shaw |

I'm not sure what I was expecting, and as we have covered before, Byam Shaw's work is not well known or well-represented in our national collections (I'm available to help with a Byam Shaw retrospective, I'll gush more than Vicat Cole), so The New Voice had to be tracked down in Vicat Cole's biography. Maud is the wistful girl on the right, apparently. I wonder if it was because she was posh, she got to keep her skirt on? Everyone else is nudey apart from the chap in hairy trousers. The group are a bunch of Pagans and Maud is being distracted by 'the new voice', John the Baptist, seen on the horizon. By this time, Maud had been exhibiting and working as an artist - her piece Don Quixote De La Mancha appeared in the 1908 Birmingham Society of Artist exhibition and was reported as 'noticeable' in the local press. I'm guessing they mean that positively, but it is a marvellous euphemism that I intend to use from now on.

In 1910, Byam Shaw and Vicat Cole founded the Byam Shaw School of Art. It isn't clear whether Maud was involved but I suspect so, as I think her sister Ethel was - in the 1911 census, Ethel was working as a 'secretary to an art school'. Maud was closely involved with the group as in 1911 she appeared with them in a rather unusual situation. It was reported in The Gentlewoman magazine that at W G Paulson Townsend's lecture on the history of embroidery, there were enacted a 'series of magnificent tableaux'. In the third tableaux, a group showed Mary Lindwood 'receiving in her studio in Leicester Square'. This was performed by Evelyn Byam Shaw, Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale, Mary Young Hunter, Hilda Spencer Watson, Joan Wodehouse and Doris Tindal Atkinson. (I've linked to posts I've done on them but I've done too many on EFB to link and I'm coming for you, Hilda Spencer Watson...)

|

| from Lady Ann's Fairy Tales (1914) |

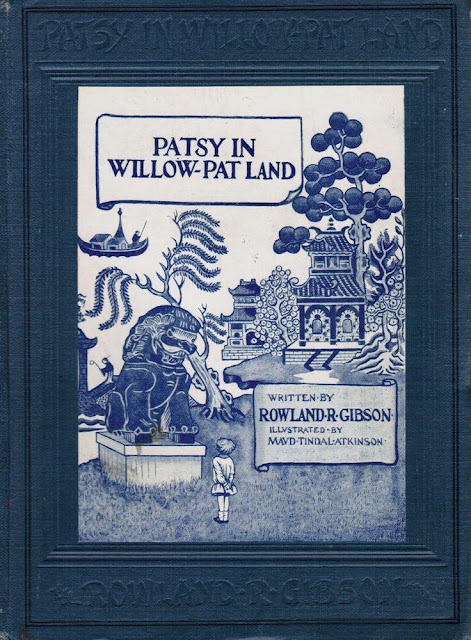

I wonder if Maud purposefully specialised in book illustration or if those jobs came along so she did them before exhibition work? Either way, the 1910s were full of illustration work of such quality that Maud was included in a 1969 exhibition on the finest British Book Illustrators alongside Walter Crane and Aubrey Bearsdley. In 1914 Maud provided illustrations for Lady Ann's Fairy Tales by Lady Catherine Milnes Gaskell to much acclaim - The Daily News commented that Maud worked 'in the Pre-Raphaelite manner', which I don't think is particularly evident in the above illustration but tells you a lot about critics in 1914. In other newspapers, the drawings are praised as 'very pretty' and 'beautiful', however, I am absolutely in love with her 1916 illustrations for Patsy in Willow-Pat Land by Rowland Gibson...

I mean, look at it! Rossetti would have kittens, it's so glorious, but so far I can only find an illustration of the front cover. Willow-Pat Land sounds absolutely worth a visit, as does the location of her 1921 offering, The Land of Nice New Clothes by E H Paine. I actually own her 1922 volume My Favourite Nursery Rhymes, edited by Samuel J Looker, and she showed influences as diverse as Kate Greenaway, EFB and Mabel Lucie Attwell...

Glorious! In 1926, she illustrated The Beautiful Childhood, her illustrations described as 'particularly beautiful and will convey to the youthful mind a fuller appreciation of the story which tells the Life of Jesus through his first 13 years,' by the Yorkshire Post. She also provided 'graceful' (according to The Scotsman magazine) illustrations for Dion Clayton Calthrop's "I Will Be Good!", a Victorian memoir of a childhood. Although she obviously had a talent for illustration, Maud exhibited some fascinating pieces during the 1910s and 1920s...

|

| Ariel (c.1915) |

While it doesn't seem to have made the papers in 1915, Ariel featured in Beatrice Phillpott's 1970s book on Fairy Painting and is a very unusual take on the Shakespearean subject. Her grandfather had been a Shakespearean scholar (according to the Morning Leader 1896) which might account for the rather novel moment of Ariel's awakening/hatching which comes across as more Greek myth than The Tempest.

|

| The Balcony (undated) |

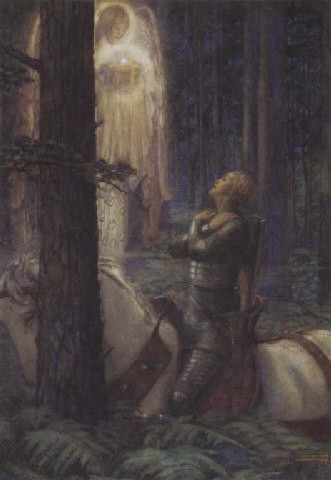

There is a watercoloured sweetness to her work, possibly jarring a little with the 1920s. A number of her pieces did justify her 'pre-raphaelite' tag, such as Galahad from 1920...

|

| Galahad (1920) |

Come on now, surely that's G F Watts from around 1860? While Ariel and Galahad had enough mysticism and luminosity to be acceptable in the modern world, I was surprised by the surprise shown towards The Drum, shown at the Royal Academy in 1929...

|

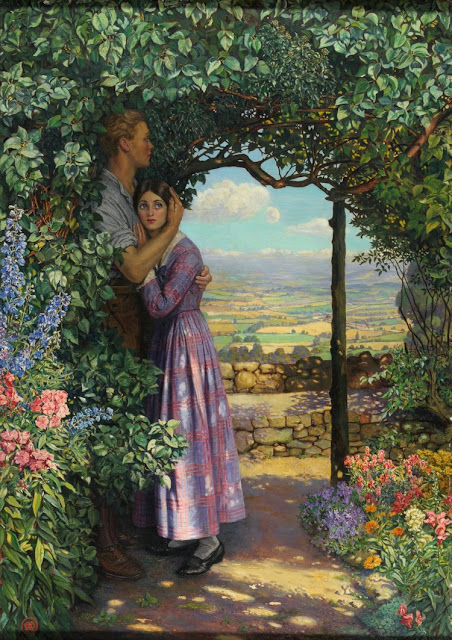

| The Drum (1929) |

Also known as The Call of the Drum, it shows a mother and daughter in a lush garden tensely reacting to a drum, presumably that of the army approaching or taking away their menfolk. The figures of the women are at odds with the beautiful, slightly chocolate-box-y surroundings and the girl looks very worried. Is it a comment on how war impacts on women, left in their little paradises? Painted over a decade after The Great War, is it an image of how fearful people were that the call would come again and remove all the men from their homes? I wonder if it was a comment that while men make war, women remain at a distance, trying to keep life going, which would certainly have been the experience of the majority of women at that time. Either way, The Scotsman, in their review of the RA exhibition wrote the piece was 'so remarkably Pre-Raphaelite in every detail that the astonished visitor will cry "Arthur Hughes or the Devil!"'

|

| The Long Engagement (1859) Arthur Hughes |

|

| The Consecration of the Round Church, AD1185 (1912) |

|

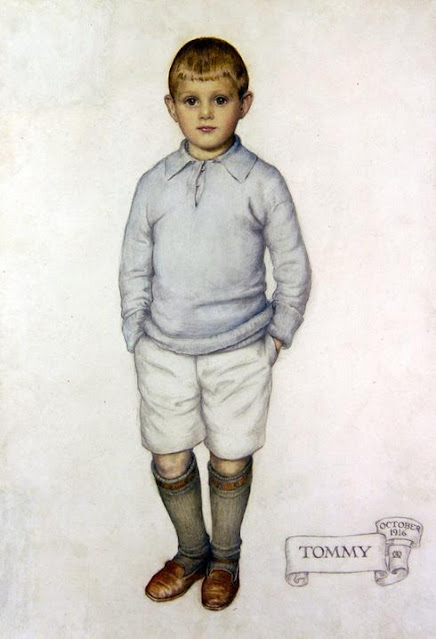

| Tommy (1916) |