The victim of my interest this week wasn't actually married to an artist - I know, that makes a change as I appear to be obsessed with artistic couples at the moment, but I met her while researching last week's post on the Cockerell family. I already knew of Sydney Cockerell, erstwhile cousin of Christabel, but I had not come across his wife before, and I certainly hadn't seen her wonderful Pre-Raphaelite inspired work. If I ever end up doing Girl Gang 2 (Pre-Raphaelite Girl Gang Rides Again!) I will have to include Florence Kate Kingsford...

|

| Atlanta's Race (1890s) Florence Kate Kingsford |

Florence Kate Kingsford, known as Kate (as the family did the thing where you are actually known by your middle name - my mother's family did the same thing and I didn't realise it was so common) was born in May 1872. She was right in the middle of seven children, preceded by Maude Clara (1867-1955), Charles Hugh (1869-1890), and Annie Grace (1871-1953), then followed by Norah Bertha (1874-1961), Olive Gertrude (1877-1940) and finally Marjorie Joan (1883-1974). As you will see, all the sisters made decent ages, but Charles was barely 21 when he died. Considering the Cockerell family connection to mining, it is quite a coincidence that Charles was studying engineering and visited the Polyear Mining Company in Cornwall, in order to see mining in person and to study the engineering of it. He was crushed in the mine when a large rock fell on him and he died a week later of his injuries.

|

| (Marjorie) Joan Kingsford Reading (1890s) |

Kate's father was a 'merchant' who seemed to sell corn and flour, an extension of what seemed to be an ancestry of millers. By the turn of the century, he had moved into financial transactions and obviously had social aspirations for his family. Unfortunately, that meant that none of the girls had decent educations, schooled only in music and singing and generally being middle-class hostesses (which reminds me of the sort of upbringing that Julia Margaret Cameron and her sisters had). Mr Kingsford was known as being a great fisherman, enormous fun and he played the violin. Unfortunately, he was not a great business man and when he suddenly died in 1902, he left his wife and daughters penniless. Her lack of education would haunt her for the rest of her life, but she could draw and that would be enough to get her out of the poverty into which they had been tumbled.

In the 1891 census, Kate was listed as an 'art student' and she attended the Blackhearth, Lee and Lewisham School of Art where she won many prizes including ones for freehand work, shading from the cast, perspective, shading from models and chalk studies. Her son later wrote that she was handsome rather than pretty, but she had initiative and that took her to the Royal Academy, despite the fact she could not spell or add or make plans.

|

| Daphne and Apollo (undated) |

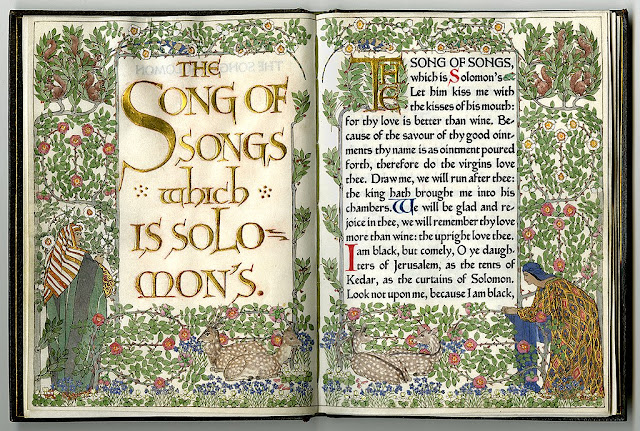

By necessity, she had to work and sell pieces and it was as one of the earlist pupils of Edward Johnston, regarded as the father of modern calligraphy, that Kate found her calling. Her work as a painter and her talent at calligraphy made her a subject of interest for Charles H St John Hornby, owner of the Ashdene Press. He sought out Kate to hand illuminate 44 copies of the Song of Songs, each with a different design. The results are breath-taking...

|

| Ashdene Press Song of Songs, illustrated by Kate Kingsford (1902) |

Flipping heck, that's gorgeous. In the 1901 census, Kate had moved to Kensington, sharing 5, Stratford Studios with fellow artist Winifred Hansard. The studio had been home to Emanuel Edward Geflowski, a sculptor from Poland, until his death in 1898 when I'm guessing the pair took the rooms. The rest of the Kingsfords had moved to 33 Dorset Square after Mr Kingsford's death, leading a more contained life, possibly with Kate offering financial support as her work was much admired. She had become a member of the Women's Guild of Art and was generally acknowledged as a leader in her art form. The Scotsman in 1906 talked about the 'exquisite and original illuminating of Florence Kingsford', and The Graphic of the same year spoke of how her work was 'so admirable in taste, feeling and execution.' In 1904, Kate and Winifred joined Flinders and Hilda Petrie in Egypt in 1904, copying the tomb paintings and producing this beautiful work...

|

| Hymn to Atten the Sun Disc (1906) |

Sydney Cockerell declared this piece to be her greatest achievement, although all of her work seems glorious. Sydney had come into contact with Kate while she worked on Song of Songs and as an avid book collector, he bought her work and made sure she always had patrons who would support her. In Wilfrid Blunt's 1965 biography of Sydney, Christopher (their son) said that Sydney's patronage of Kate kept her alive. He also understood poverty, but always found money for books and so it is unsurprising that when Sydney finally decided to marry, it would be to his favourite calligrapher.

|

| Sydney Cockerell (and cat) (c.1930) Dorothy Hawksley |

'I am engaged to be married to Miss Kingsford, the painter of Hornby's Song of Songs,' he wrote to a friend, and I find it funny that he cites her achievement as part of her name. In a 1907 letter to another friend he wrote 'I am for the moment rather absorbed in another matter, having suddenly arranged to marry Miss Kingsford. I put all the proper arguments before her, and quoted what you had said about the awful time my wife was likely to have but she persisted in accepting me.' This is really funny the first time you read it, but then reading on (in the 1965 biography), you learn that some of his friends, such as the novelist Ouida and the general git-weasel Wilfrid Scawen Blunt basically told him not to marry and that it would be a disaster. Charming.

|

| Drawing of Ellen Smith for A Christmas Carol (1867) Dante Gabriel Rossetti |

Sydney Cockerell had been secretary to William Morris, to Awful Blunt and Thomas Hardy, as well as a great collector of Pre-Raphaelite books and drawings. including the above one of Ellen Smith. He claimed he had no artistic talent, only talent for cataloguing but he cultivated many impressive friendships over his life, including his marriage. It is difficult to know other people's relationships through biography, but I do get a sneaking impression that part of the reason Sydney proposed to Kate was that he admired her art. In his diary he wrote 'in all essentials I think we are in complete accordance and I count myself very fortunate to have won so gifted a wife,' which you might say is entirely natural for someone to love you partly because you are massively good at what you do (especially if they admire the thing you do) but because of what followed, I wonder if that was the larger part of why he married her. Sydney's adoration for great men rivalled Julia Margaret Cameron but he couldn't marry one of them, so he married a great and talented woman instead. You'll see what I mean by the end of this...

Anyway, shortly after their engagement, Sydney had to travel to Scotland and he relished the chance to write copious letters to his beloved, being an avid letter writer. Kate, on the other hand, didn't do writing that wasn't illuminated and written by someone else. In the 1960s biography, it says how he chastised her for her poor spelling, her lack of details and general poor correspondence. Poor Kate did not know how to write love letters, let alone how to consistently spell her husband's name right. She wrote 'drawing...is the only mode of communication I have with the outer world.' Still, Sydney complained that she wrote to him as one might to a piano tuner. He wrote 'There is no such word as 'alright' which comes in your three last letters...do try to remember and not persist with 'alright' as you persisted with 'Teusday'' - Kate resorted to calling it 'the day after Monday'. Although Kate's lack of education seemed to horrify Sydney, some of his friends were delighted, as one wrote 'I can't tell you what a relief it is to hear she cannot spell. I thought she would write her letters in gold ink, and be too exquisite to have anything to do with the likes of me.'

A pet peeve of mine is when women do not have their profession written down in records and in their banns, Sydney is a 'bibliographer' (which feels like a pretentious way of say 'book lover') and Kate has no profession, nor will one be recorded officially for her again. Kate apparently wanted them to marry near her family in London, but none of the churches suited Sydney's taste and so he arranged for them to marry at a twelfth century church at Iffley near Oxford. The Sketch wrote 'Ruskin's ghostly blessing must certainly have fallen on a ceremony that took place a week ago...Mr Sydney Carlyle Cockerell was there married to Miss Florence Kingsford, and if ever there was a marriage of true interests here was one; for, while Mr Cockerell is in the habit of buying manuscripts, Miss Kingsford makes regular practice of illuminating them.' She was 35 and he was 40, so hardly love's young dream but a meeting of interests seems fair.

|

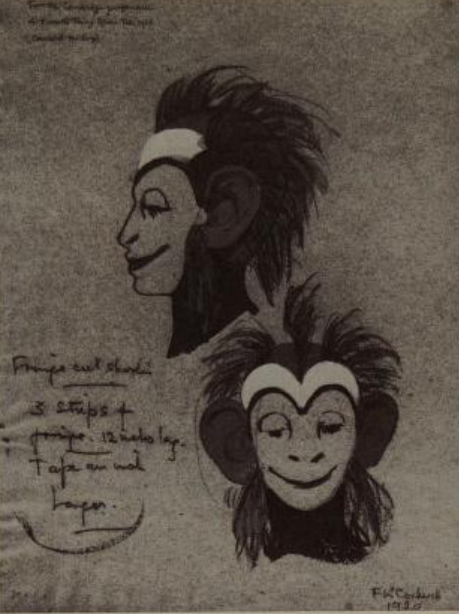

| Designs for theatrical costumes (1920) from Duet for Two Voices (1979) Hugh Carey |

The Cockerells honeymooned in Burford, at a house lent to them by Jane Morris, then to Rottingdean to stay with Georgie Burne-Jones. Sydney was surprisingly ambitious, but I wonder if he was moving from a period of hero-worship to making a mark for himself (mainly because an awful lot of those heroes were dying of old age). They moved to Richmond in the January of 1908 but by then Sydney had his eye on the directorship of the Fitzwilliam in Cambridge, which he claimed in June. By this time, Kate was pregnant with their first child and she was moved into Wayside, 15 Cavendish Avenue a cold little house with no hot-water system and not particularly pleasant to live in. It's still there if you want to Google Streetview it and I think it's the little house which looks charming now but I'm guessing without basic heat or water, it would feel a bit primitive. In quick succession, Kate had Margaret (1908-1986), Christopher (1910-1999) and Katherine (1911-1996) and no longer found that she had the time or energy for her detailed illuminations. Instead, she designed costumes for Cambridge operatic productions, such as The Magic Flute in 1911 and Purcell's The Fairy Queen in 1920. Kate's shyness meant that she did not revel in the role of hostess, despite her husband's love of entertaining the great and the good. Added to this, there was not enough money for dresses to hold dinner parties or even sherry (although always enough for Sydney's books, but I'm in a bit of a glass house there myself), but they arranged to hold Sunday afternoon tea for their guests, a far more relaxed affair. Over the years, the Cockerells's teas included guests such as Thomas Hardy, Roger Fry, Rudyard Kipling and Georgie Burne-Jones. Socially, they were successful and Sydney became one of the most iconic museum professionals of the twentieth century.

|

| Kate and the children, 1920s |

It is interesting that reading her scant obituaries and mentions in Sydney's biographies, it is assumed that she stopped working at her diagnosis but this is not really the case. At the birth of her children, Kate found her time stretched too thin, leading one writer to comment that all her work was done in the span of a decade, I'm guessing around 1900-1910. In that time she produced 60 books, but her work was cut short by children then ill health. She kept working as long as she could; for the production of The Fairy Queen, Kate had the help of her sister Joan in designing the costumes and drawing out the designs. Sydney borrowed Thomas Hardy's bath chair, but the man they employed to push Kate around in it was run over by a milk float and Sydney just couldn't find the time (or inclination) to push his wife.

The fact that we know anything about Kate after her illness is due to the fact that Sydney kept a diary, but after a certain point, he stops mentioning her at all, as if she has ceased to exist. In the 1960s biography (which had input from the Cockerell children), there are instances where Katherine, their daughter, tried to get Sydney to take Kate on holiday but he refused. He seemed to continue to live a very separate, professional life from his wife and home. In 1937 the couple moved to Kew, to Charles Shannon's old house, which had an excellent ground floor room for Kate. Kate built a life for herself apart from her husband, printing books in braille, sewing, knitting and playing cards with her neighbours. Even the war did not really touch on her life, and her children grew up, all three married and grandchildren followed in the 1930s and 40s. In July 1949, Christopher arranged for his mother to go on a three-week holiday to his home in Danbury, but on her return, Kate suffered a stroke. She was taken to the Nightingale Nursing Home in Twickenham where she died on 18th September 1949, aged 77.

|

| Sweet Thames Run Softly (1900) |

Some of you might recognise the name Christopher Cockerell, especially if you hail from my neck of the woods on the south coast. He was the inventor of the hovercraft, and in 1974, he approached the Fitzwilliam Museum to donate a collection of his mother's books and sell them some of her pieces as well. From a collection valued at £6K, they were asking £4K and the books were in an exhibition that ran through that summer. Christopher made sure there was a complete account of his mother's work, her talent and exceptional qualities all reported, linking her name to that of William Morris and Edmond Dulac. Her work is held by the museum today.

It's hard not to feel disappointed in how inadequate Sydney was in caring for Kate, even before her illness. There was seemingly no room for her talent, which he admired so much, in their marriage, or at least he did not seem able to conceive how to accommodate it, but then it was a different time when the idea that a man would share parenting duties so that his wife could work would have seemed wildly bohemian. I will grudgingly give Sydney credit for exhibiting Kate's work and taking it on his travels so that her work was seen in such illustrious places as the Louvre and would continue to be commented on in the newspapers because he gave it exposure. I won't therefore be unkind to Sydney Cockerell as he himself said in 1907 that he would be marrying 'Miss Kingsford the painter' and that is who he never stopped admiring. It is a shame for Mrs Cockerell, his wife, that he could not show her as much attention as her books.

_poster.png)

.png)

.jpg)