Occasionally, Mr Walker, in his infinite wisdom, will say to me 'what do you know about so-and-so?' Now, normally I can give him something, after all these years we have been doing this nonsense, you and me both will have heard of an awful lot of artists. However, on occasions, I must quietly admit, I come up entirely blank. These are the moments Mr Walker give an evil chuckle as he knows he won't hear a word out of me until I know everything and he at least will get a bit of peace and quiet for a change. So, thanks to Mr Walker, here is a post on Theodora Joan Noyes...

|

| Portrait of a Lady in Black (c.1900) |

Theodora, or Dora, Noyes (1864-1960) was the twelfth and last child born to Samuel (1820-1890) and Charlotte Noyes (1820-1896). Samuel was a solicitor, so I'm assuming they could afford the large family and a surprising number of the children lived very long lives. After Samuel and Charlotte's marriage in 1845, their offspring were Charlotte jnr (1846-1929), Harry (1848-1917), John (1849-1864), Mary (1851-1949), Edward (1853-1921), Charles and Frederick (1854-1877, yes, we'll come to that), Herbert (1855-1879), Katherine (1858-1930), Robert (1859-1923) and Margaret (1863-1949), followed finally by Dora. John died in his teens, and the twins and Herbert in their early 20s, but I was surprised by how some of the sisters lived into their 90s. I'm always blown away by how much must have changed in their lives, for example Dora was born before Rossetti met Alexa Wilding and by the time she died, we were headed for the moon. Flipping heck! I digress. Let's start from the beginning...

Dora was born in Harrow-on-the-Hill in Middlesex, just outside London. The family seem to have lived in London for a while with the eldest children being born in Belgravia and Mayfair (which tells you how wealthy they were) before moving out in around 1849 to the village of Harrow-on-the-Hill. The family seems to have moved around a bit more, all to very nice addresses, before moving back to Hanover Square in Mayfair in time for Dora to attend the Lambeth School of Art.

|

| Students drawing from a model at Lambeth (c.1910) |

There is a very helpful piece on Lambeth in the Every Woman's Encyclopedia from around 1910, which reports that Lambeth School of Art opened in 1860, built on the site of the old Vauxhall Gardens and by the time Dora attended in 1880, there had already been the likes of Charles Shannon and Stanhope Forbes as pupils (although Shannon might well have been there around the same time as Dora). Dora received the third grade prize and the book prize for drawing from life but also excelled at lace work, embroidery, spinning and weaving. She also attended art academies abroad, including a spell in Paris, as well as the RA school. I have to admit that the majority of the information I have about her early life comes from her obituary as, despite being very successful as we will see, she kept a distinctly low profile. I actually learned from that excellent publication Building News that Dora won a medal from the Royal Academy of Art school for drawing of a statue or group and £10 for a drawing of a statue or group executed within the year in the Academy.

Just a pause in her career here to point out that although Dora was only one year old when her brother John died in 1864, she was 12 when the twins Frederick and Charles died within 2 weeks of each other, which must have been a massive shock. I was hoping for some illumination in the newspapers but there is nothing so I'm guessing it was either a shared illness or one died and the other died of a broken twin heart. This was followed 2 years later by the death of a third brother, Herbert, over in Admedabad in India. He had been a Captain in the 10th regiment of the BNLI and died of cholera. By the 1881 census, brother Edward was in the Ceylon Civil Service, with Harry working as a solicitor like his Dad and Robert as a solicitor's articled clerk, all very legal. None of the daughters had any sort of occupation apart from being a wealthy man's daughter, nice work if you can get it. Moving on...

Dora debuted at the May Royal Academy exhibition in 1883 as Miss Dora Noyes of West Hill, Southfields, exhibiting two paintings, An Old Fatalist, an oil painting and A Study in the etchings, drawings and engravings gallery. The next year she was back with another oil, Phillis. At this point, me and Dora are going to have a little chat as when she returned to the RA in 1887, she was listed as Miss T Noyes in the index (not helpful), having moved to Trafalgar Studios in Chelsea, showing Noonday. This was the piece that got her attention, as the Magazine of Art reported 'a good study of a peasant girl somewhat in the manner of Mr Clausen is shown by Miss Theodora Noyes ... Here the modelling is not so sound as the drawing, but the colour is very pleasing and the landscape is broadly presented and cleverly subordinated to the figure.'

In 1889, Dora is listed as living at 18 Finborough Road and that year she had three oil paintings in the RA's May exhibition, Sea Poppies, Santa Lucia and The Year's At The Spring. Despite this splendid effort, she garnered absolutely no press whatsoever. We're also a bit early for those everso helpful books of pictures which are on Archive.org, so we'll have to wait a few more years for her not to appear in them either. Her 1890 RA paintings were Miss Noyes which I'm guessing is one of her sisters, and The Old Miniature, again neither of which I have to give you, but I'm wondering if the former remained in the family.

|

| A Rest by the Wayside (Resting at the Gate) (1891) |

A year later, she was back with three more paintings; A Rest by the Wayside, Mrs Cecil St John Mildmay, and Autumn Pastures. She also appeared at the Dudley Gallery in the exhibition of the New English art club with Poppies, which the Queen magazine called 'delightfully clever' and the Illustrated London News praised for its splendours and difficulties. Her painting A Rest by the Wayside also sold for £31/10s, the equivalent of around £2,500 today. The Lady's Pictorial praised its excellent qualities being 'very well drawn and natural in action.' The Bath Chronicle likewise praised the painting recognising its modern French influence.

A quick note about her family situation, as both Samuel and Charlotte snr had died by this point, meaning that in the 1891 census Harry had become the head of the house, with sister Mary (living on own means) and Theodora (Sculpt. Artist), all living on Warwick Street, Belgravia (actually alarmingly close to Piccadilly Circus and so it looks like a hellscape these days, no doubt still horrifically expensive.)

|

| Two at a Stile (1894) |

In the autumn of 1892, Dora exhibited "I was a Stranger and ye took me in" in Liverpool (shown again in 1893 at the RA), described as being a scene where an elderly couple find a faint girl clinging to their wall. The RA exhibition of May 1893 also included Hayraking, and Summer-time but the narrative piece was definitely the star of the show. Similar to Rest by the Wayside, her 1894 painting Two at a Stile also was popular choice at the RA, due to the quiet narrative of the rural couple and their possible romance. She also had Apple Trees and A Hedonist in the May exhibition but it was the couple and the stile that got the press interest. Dora moved out of London to Salisbury in Wiltshire during 1894, listing her address in the 1895 RA catalogue as Milston, just outside Salisbury in Wiltshire. Here she was inspired to paint Wiltshire Weeds, one of paintings in the RA that year, as well as a portrait of a child, Hester.

Interestingly, her 1896 RA entry Miss Gina Goldingham received absolutely no press coverage that I can find and I don't know who Gina was, which also might have contributed to the lack of interest. Likewise, despite having two paintings in the RA in 1897, The Enchanted Hour and Peace, the press were disappointingly quiet, which is a shame as I really want to know what The Enchanted Hour was all about. However, in 1898 she exhibited a painting called The Queen's Jubilee, I'm guessing for Victoria's Diamond Jubilee the year before, which the Black and White journal declared to be one of their pictures of the year. The end of the century also began one of the reasons why Dora has been overlooked as an artist - she became a very accomplished illustrator. 1899 saw the publication of Frith and Allen's The Science of Palmistry, which can be viewed here.

|

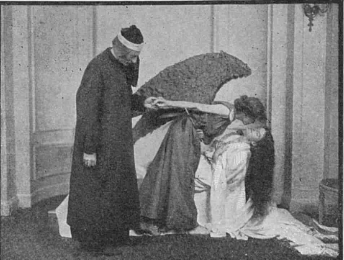

| The Silent Life (1900) |

In 1900, Dora showed The Silent Life at the Royal Academy, which the Lady's Pictorial called 'quiet and effective'. It reminds me very much of Charles Collins' Convent Thoughts or Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale's image of Guinevere in her nun garb. I think it is likely it was inspired by her eldest sister Charlotte who had become a Sister of Mercy at the All Saints Convent in St Albans. Dora was back in 1901 with a portrait of the children of someone called Rex Howell, but she was also illustrating her sister Ella's book on the Saints of Italy. The Scotsman's verdict was 'Thus the Old Masters are interpreted for the young misses, and the Golden Legend suitable alloyed for the practical purposes of spirited commerce in a pious nursery.' May all your nurseries be pious...

|

| Illustration of the Palazzo Il Moro from The Story of Ferrara |

Briefly, Dora moved down to Torquay and in 1903 exhibited Miss Jane Helen Findlater who may be the novelist Jane Findlater who worked with her sister, much like Dora and Ella. The following year, Ella and Dora published The Story of Ferrara (which you can see here) As it is quite difficult to find the sisters at this point on census, I wondered if they were travelling in order to research their subjects. In 1905, the sisters produced another 'travel' book, The Casentino and its Story, which was marketed as a half-guinea colour book.

|

| Haymakers from Salisbury Plain (1913) |

|

| A Ploughing Scene (1895) |

While we merrily gallop to celebrate female artists of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, Dora Noyes reminds me that we have to be able to see them before we can cheer for them and like Dora, I bet there are so many more amazing painters who are waiting, unseen.

.jpg)

.jpg)