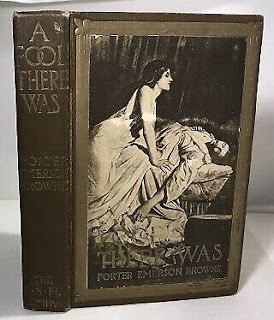

I've gone with a very upbeat title for this because this is a bit rough. It's about a sculptor, a model, celebrity and a Wikipedia entry that made me wince. This is the story of the exceptionally talented Mary Redmond and the appalling incident that made her a star.

Mary Redmond was born in Nenagh, County Tipperary in 1863. Her father was the overseer of a stone quarry so, as one dreamy article on her life stated, she was 'bred within sound of the stone-cutter's ringing hammer.' Pace yourself there, it gets far more flowery, I warn you now. When she was 5, Mary found clay around the quarry and wanted to make little pots for her dolls house. She sculpted them, then filled them with water before placing them on a fire. They obviously crumbled to bits, but she was not discouraged. Finding better clay she tried again and again, moving on to people. A local elderly woman fascinated her, so she sculpted her, including the frills on her strange high cap. With her little hands, she found manipulating and softening the clay difficult, so she bit and chewed it to work it. A period of illness (hopefully not connected to chewing clay) followed and when she recovered she found she had lost her best sculpting teeth and so had to wait for her adult teeth to come through before continuing with her art.

She decided to be a sculptor at 11 but was equally talented with drawing. The New Ross Standard recorded that she was a accurate caricaturist 'Woe betide the luckless teacher who did not appeal to her sympathies! A few deft strokes of her crayon or a little figure quickly rising out of clay under her magic touch and the whole class would be in an uproar of laughter.' Mary created a whole trayful of female figures which were admired by people who came to see them. She was unable to model them with feet so none of them could stand, so it was suggested that she had a go at modelling 'the extremities'. Mary got her little brother to take off his sock and she modelled a foot and showed it to Mrs O'Meara, the wife of a neighbouring rector. Mrs O'Meara was so impressed she enlisted the help of two sisters called Lawless, who were the sisters of Lord Clonary. It was agreed that little Mary should be sent to the big city, Dublin, where she could get a proper art education at the new Metropolitan School of Art. Aged only 9, with only a very basic education up to that point, Mary was admitted to the Kildare Street School of Art. Miss Lawless, one of the sisters, kept an interest in Mary, paying for her to live in Dublin so her artistic ambition could continue.

Robert Edwin Lyne took one look at Mary and said she was too young to attend the Metropolitan School of Art. Mary replied she was much older than she looked, although she was very small. She did not like drawing at all, but was allowed to bring in her own clay and sculpt. At that time, there were no formal sculpting classes, but once settled in, she exceeded at drawing and earned scholarships that would see her all the way through her education. She worked for local businesses, decorating ceramics and even teaching classes, despite being barely over 20. Rosa Mulholland, a well-known Irish novelist, visited her in one of her classes and was astonished to find 'a little pinafore-girl out of a nursery, in a white over-all blouse, with a cropof short curls across her forehead. I then thought the little maid in her workshop one of the prettiest sights I had ever seen.' Not only that, Miss Lawless provided the money to continue her education abroad and sent her off to Italy.

Her departure was reported in the newspapers, such as the Freeman's Journal in 1886. Miss Redmond was leaving for Rome for three years for the purpose of pursuing her further studies under the guidance of Italian masters, and she took the hopes of her community with her. She boarded in a convent, as reported by the Dublin Daily Express in December 1889, enjoying the heat, the fountains and the pomegranate trees. When she became ill, she moved the the cooler climate of Florence, and the school of the Belli Arti under sculptor Raffaello Romanelli. While away, she had arranged for her works to continue to be exhibited and in 1888, the Corporation of Liverpool purchased her studies in terracotta for 'the local museum' which had been shown at a recent exhibition. At this point, Mary was in Florence and here she met two important people. The first was William Gladstone, whose bust she was commissioned to sculpt on her return in 1889. The other was a dentist, Dr William Dunne, also from Ireland, who she fell in love with and would eventually marry in 1893. However, despite being reasonably well-known at this point, the next few years made her famous for more than her talent.

|

| The Martin Memorial |

On her return, Mary plunged back into work, travelling to London to sculpt Gladstone in a fortnight and gaining commissions to design a memorial for the late District Inspector Martin, who had been killed while attempting to arrest a priest. She also sculpted a bust of Edmund Dwyer Gray MP, who had died in 1888, and 30 marble copies were ordered as it was so popular. Rosa Mulholland visited her again in her studio in Dublin, describing her in an article as 'quite grown-up, though still small and child-like with a pretty face, a quick glad manner of speech, a bright, brave glance, and as altogether as bonny a little person as ever travelled from Dublin to Italy and back again.' Her name also appeared on a letter in favour of female suffrage that appeared in the Fortnightly Review in July 1889, alongside fellow artists Louise Jopling and Isabel Dacre. Mary was now 26 years old and as she had done before, submitted a design to a competition to design a statue for Father Theobald Mathew, the Apostle of Temperance...

|

| Theobald Mathew (undated) Edward Daniel Leahy |

Theobald Mathew (1790-1856) had been a Catholic Priest and teetotal reformer. Born in 1790, he had founded the Catholic Total Abstinence Movement in Ireland in 1838, as the 'Knights of Father Mathew'. For the centenary of his birth, it was proposed that a statue be raised in his memory and a competition was launched to which many entries were submitted. The choice came down to Mary and Herbert Barnes, with Mary's design ultimately winning over the committee, for both artistic reasons and that she was charging them a lot less. Although this shouldn't have had any influence, the committee's next job was to raise the funds for the statue, so it definitely played a role. Donors such as John Mason Cook, the famous excursionist and son of Thomas Cook, gave money and wrote letters in praise of Father Mathew's efforts. It was also proposed that all pubs would be shut for the day on 13th October in remembrance of his work. Mary's statue was of Father Mathew in his Capuchin Order of Friars robes posed with his right hand raised 'as if in accompaniment of words of exhortation', as the Irish Independent newspaper recorded. The Irish Times reported on a public meeting from May of 1890, how the statue of the man known as the Apostle of Temperance would be welcomed as he was gratefully remembered in Ireland for his noble works. The statue was planned to be placed in a leading Dublin thoroughfare, O'Connell Street, where plenty would see it. The money was raised and Mary attempted to find a model suitable. Finding a male model in Dublin was apparently a difficult task, but she was advised to try the Night Asylum, a homeless shelter. There she met Richard Hunter, 23 years old and absolutely perfect in looks. He had been a gentleman's valet to someone who Mary knew and who was given good references and so Mary hired him.

Richard Hunter was quiet and obedient, respectful and constantly going to mass and confession and gave the impression of a sober, well-behaved, handsome young man. Mary remembered him as a splendid model, falling into the perfect poses at only the slightest of suggestion. As she told the reporter for the Irish Society journal of 1891, Hunter suddenly changed from being quiet and respectful to surly and threatening. On top of this, his pose, as she said, was 'spread', a studio term for a lack of compactness. Unable to work with him, Mary sacked him. He returned the next day, full of remorse, but as the model for the statue was almost done, Mary refused to rehire him. At that point he threatened her work and vowed revenge.

What happened next is why I wanted to write this post. According to Mary's brief Wikipedia entry, 'the male model for the Father Mathew statue took the concept of getting plastered a little too far, was dismissed for drunkenness and was later convicted for vandalising her work.' I can understand the contemporary accounts minimising what happened, but the details of Richard Hunter's revenge were written in detail in the newspapers and it was a little more than just vandalism. Up to this point, Mary's story has been one of her single-minded, individual rise from humble beginnings to competing at the top of her field, while still in her early twenties, without family money or a husband as a safety net. That independence, much commented on in news reports, might have played a part in Hunter's antagonism. Her tiny, child-like build might have also meant he thought he had the upper hand. However, things did not go exactly the way he thought.

On 26th May 1891, with the work on the statue all but complete, Mary returned to her studio on Great Charles Lane at 8pm. She lived not far from it, at Fitzgibbon Street in Dublin and it had been a week since she had dismissed Hunter. At that point, Mary noticed that a linen coat had vanished and when asked, Hunter denied it, another reason why Mary refused to take him back as it had only been the two of them in the studio. As she put the key in the door, Mary heard someone running towards her and as she turned she found Hunter next to her, wearing the stolen coat. He punched her in the face, then in the back of the head, shouting 'Now I have my revenge; I destroyed the statue!' Mary fled back towards Fitzgibbon Street, meeting her maid who she sent for a policeman. The maid fled and didn't return, so another friend fetched the police who caught Hunter. Hunter denied any involvement but once at the station, not only did he admit to criminal damage and assault, his chilling words were recorded and read out in court the next morning - 'I will only get twelve months for this, and I will take her life if it takes me seven years.' He also regretted that he had not strangled her in the studio or carried a knife to kill her. On entering the studio, Mary found her model smashed to atoms, all her work destroyed.

It went to court and was an absolute sensation. Mary's fame and the violence of the attack, not just on Mary but also on the effigy of such a beloved figure made headlines. Hunter pleaded guilty to the attack and the destruction but denied taking the coat, which had again vanished. He was found guilty of everything with revelations that he had been in trouble with the law previously including three months for larceny, 4 days in prison for drunkenness and 2 weeks for 'illegal possession of a coat'. Coats were obviously a thing for him. When he received his sentence it was 14 years imprisonment, twice the seven years he promised to take to kill Mary.

Mary had a mammoth task, to recreate her statue and in the May of 1892 the committee came to her studio to see the 9 foot clay cast of the statue. Everyone was even more impressed than they had been before, telling the Irish Independent newspaper 'Miss Redmond has worked at her task with devotion and the result of her efforts must indicate, in the eyes of all who appreciate Irish art, the gifted lady's claim to those qualities of hand and heart.' The piece continued by quoting an anonymous poem addressed to painters about to illustrate the labours of Father Matthew - 'Seize thy pencil, child of art! Fame and fortune brighten o'er thee, Great thy hand and great thy heart, if well thou dost the work before thee.' Mary's work was done and nine months later, the finished statue had been cast and placed on the plinth. The unveiling happened on 8th February 1893, with Mary present to see her massive priest unveiled. She was celebrated not only as the creator of this landmark but also as the youngest sculptor of a piece of public art. Shortly after, Mary travelled to London to marry Dr William Dunn who she had met in Florence. The couple went back to Florence where they lived a long and happy life together, with two children; a son who survived the First World War with honours and a daughter who followed her mother into art. Apparently, there are two small marble angels in the chapel of the Order of the Little Company of Mary in Florence that were created by Mary and her home, within sight of Galileo's Tower held a warm welcome for any Irish traveller, including Joseph Plunkett the novelist, who recorded a visit to her home in 1911 and their trip to see art in Naples. She died in 1930 but received obituaries back in her native Ireland, remembered still for both her talent but also the destruction of her model. It seems that forty years later, the outrage was still felt.

When I read the mention of the attack on Wikipedia, I was astonished. I had read the newspapers first and then went looking for her. Honestly, as you can see by the lack of illustration, Mary does not have the presence on the internet that you would think, considering she was such a celebrity. There are a number of places where her work is ascribed to someone else - without fail, a male sculptor. However, I was concerned by the lightness over the attack. Mary was a young woman, very young and without protection or family, working in a male dominated industry, competing and winning against her male peers. The attack on her was brutal and could well have been fatal as that was Hunter's intention. It is passed off as a moment of drunken madness in modern accounts, but no mention of alcohol is made in the majority of the accounts of Hunter, and certainly none from the night of the attack. You'd think that the newspapers would have had a field day if the model for the Apostle of Temperance had been drunk, but it is not mentioned at all. On the contrary, Hunter's clarity of his intentions are chilling. As we see from people like Dolly or Ellen Smith, that violence can come to define a woman's life and in a way, Mary Redmond's work is still mentioned in the same breath as her attack. I'm not sure how I feel about that, and sadly it's because violence in women's lives is so common that it seems a little redundant to be excited about it. However, violence seems to exist as a shared secret, something we do not talk about and maybe we should, not just the violence towards Mary or Dolly or Ellen, but against women we know, women we are. Being a woman seems to mean experiencing violence, which is a tragedy, but it also means surviving, thriving and succeeding.

It can't hurt to acknowledge both of those things.

.jpg)

.jpg)

_Publicity_Still.jpg)