I was very fortunate in my first job after I left school. I worked as a part-time administrator at Devizes Museum, in the centre of Wiltshire, and a more lovely place filled with cheery, mad people you will never find. I was spoiled for the rest of my working life, although my current place of work does come close in terms of insanity and loveliness. It was while I was working at the museum that we hosted an exhibition of work by Graham and Ann Arnold, Graham and Annie Ovenden and David Inshaw. I was young and entirely stupid, and had no idea who they were, but when I saw their art my jaw hit the floor and was never to rise again. I had seen work by the former Brotherhood of Ruralists, and I loved it.

Have you ever heard of the Ruralists? I’m not going to judge you if you haven’t, but as a fan of the Pre-Raphaelites, I guarantee you will love it. Formed in the mid 1970s as an escape from the urban life and a celebration of William Blake, Samuel Palmer, Shakespeare and poetry and literature of the nineteenth century.

|

| Fairy Child Crying (c.1972) Peter Blake |

Now, you might of heard of Peter Blake – he was responsible for the ‘Sergeant Pepper’ album cover for the Beatles. He had been a proponent of Pop Art, but joined the Ruralist revolution, creating some beautiful powdery pictures, filled with mystery and magic.

| |

| 'Well this is grand!' said Alice... (1970-71) Peter Blake |

Graham Ovenden is instantly recognisable in the airbrush-y softness of his canvases. He claimed that ‘Ruralism is a conscious effort to regain at least a modicum of grace.’ Well, sigh and swoon, what a lovely sentiment. Not only do his paintings give a sense of a striving for some unreal, misty world, but his photographs are beautiful, if on occasions unsettling. More than just photographs to paint from, they are works of art in themselves.

|

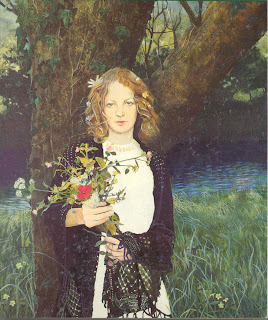

| Ophelia (1980-81) Graham Ovenden |

|

| Sam (1972) Graham Ovenden |

I have to admit to loving Annie Ovenden’s image of Ophelia almost as much as I love Millais’.

|

| Ophelia (1979-80) Annie Ovenden |

I love Ann Arnold’s Wiltshire Wedding as it reminds me of Devizes, I believe it is a picture of St John’s churchyard with the roof tops of the Museum in the distance. It also reminds me of the 1960s film of Far from the Madding Crowd, also filmed in Devizes.

|

| Wiltshire Wedding Ann Arnold |

Graham Arnold’s work is astonishingly precise and clear, and there is a set of unique collage/mixed media pictures, filled with tiny details that make you stare for hours. It reminds me of Kit Williams, and I loved Masquerade when I was a child, I wanted that golden bunny....

|

| The Dream Child (1990) Graham Arnold |

|

| I never stood a chance... |

Arnold’s works on the theme of Alice are both odd and traditional in equal measures and I find them the most compelling of all the Ruralist’s works on Wonderland.

Finally, I come to David Inshaw. I have The Badminton Game hanging in our hallway, again it reminds me of my home town and the backs of the Georgian houses you can see as you walk up the banks of the Kennet and Avon Canal, into town.

|

| The Badminton Game (1972-73) David Inshaw |

I had the good fortune and pleasure to see David again after a very long time last Friday at the opening of an exhibition at The Wiltshire Heritage Museum (formerly Devizes Museum) and he has the most beautiful picture, Hardy’s Path – Woman Running, in ‘Landscapes of Thomas Hardy’s Wessex’, which runs until 29th August, and if you can I do urge you to go and see it.

Why am I talking about a group of living artists when I am so pathologically rooted in the past? I’ll give you two reasons. Firstly, their work consciously echoes the themes and style of Pre-Raphaelite art, the epitomy of this being Graham Ovenden's reimagining of Holman Hunt's Miss Flamborough

|

| Miss Flamborough (2005) Graham Ovenden |

|

| Miss Flamborough (1882) William Holman Hunt |

Secondly, imagine for a moment it is 1848 and you got to meet Millais, Holman Hunt and Rossetti. Sit down if you need to. OK, well, I feel the same way about having met the Arnolds, the Ovendens and David Inshaw. These artists are amazing, create the most beautiful and inspiring works and are from the same place and time as we are. It gives me hope, it makes me feel less alone in my utter loyalty to a past sentiment, a bygone love of beauty and grace. The artists walk among us and we should feel better knowing it.