Another title for today's post could be 'a painting and a dance and a silent movie' as that is where we are going with this one. It all begins with this mysterious painting...

|

| The Vampire (1897) Philip Burne-Jones |

Please excuse the crappy black-and-white illustration but that is part of the mystery. This is arguably the best-known painting by Philip Burne-Jones, son of Edward, and after five years work, it was exhibited in 1897, coincidentally the same year that Bram Stoker published Dracula. Philip actually sent Stoker a postcard of the painting, with a cheeky quip about his lady vampire evening out the gender balance with Dracula. In the same exhibition as The Vampire was Edward Burne-Jones' Love and the Pilgrim...

|

| Love and the Pilgrim (1896-7) Edward Burne-Jones |

Even though Edward Burne-Jones' gentle romance would have been seen as an oddity by the end of the century, it was Philip's painting that was the talking point and mostly not for good reasons. The Dundee Advertiser, on 24 April 1897 commented that 'the subject is a ghastly one, and the artist has intensified its repulsiveness.' The Westminster Gazette called it 'both unsuccessful and unpleasing' - 'he has skill and a certain originality, but he must do something better than "The Vampire" if he is to prove worthy of a great name.' Many papers commented on the fact father and son were shown together and the staggering differences in the works. Also commented upon was the accompanying poem for The Vampire, written by Philip's cousin Rudyard Kipling. I won't reproduce it all here, but if you fancy a read, it's available here and was reproduced in the New Gallery catalogue, much to the bewilderment of the critics. As the Truth newspaper commented, Kipling's verse didn't 'assist one to a much clearer knowledge of the meaning of "The Vampire"' but nevertheless, it might serve as a model to make future exhibitions more interesting. The verse that was reproduced the most, and caused the most trouble was the first one...

A fool there was and he made his prayer

(Even as you and I!)

To a rag and a bone and a hank of hair

(We called her the woman who did not care),

But the fool he called her his lady fair

(Even as you and I!)

(Even as you and I!)

To a rag and a bone and a hank of hair

(We called her the woman who did not care),

But the fool he called her his lady fair

(Even as you and I!)

So, the gist of the poem is that the poet knows a man who has had his life sucked out of him (metaphorically) by a terrible woman, 'the woman who did not care'. The woman in question is seemingly unaware of the effect she has or the amount she demands of her lovers and is slowing killing her suitor, thoughtlessly. In that way, it doesn't seem to match the painting which has a very aware soul-sucker, however the effect is the same and both poem and painting elicited excitement due to the bitterness and also because the Vampiric lady looked anywhere between 'a bit' and 'exactly' the actress Beatrice Tanner, better known as Mrs Patrick Campbell...

|

| Mrs Patrick Campbell reading the Kelmscott Chaucer (1904) William Smedley-Aston |

Now look, I'm not one to gossip (I massively am) but it seems that Mrs Pat had been having an affair with Philip and was a very close friend of his Dad who she called 'Dearest'. Kipling knew of his cousin's infatuation and subsequent dumping (as did everyone) and so people not only assumed the woman in the picture was Mrs Pat but that it was absolutely dripping with juicy scandal. The Era on 1 May 1897 reported that the woman (who shall remain nameless) (she's an actress) was considering litigation. As it turns out, when asked later, Mrs Pat said she hadn't even seen the picture, and was away from London at the time, but in the Pall Mall Gazette of September 1897 she said she was not offended - 'Indeed I am only too glad to hear of the young artist's success'. It's worth noting that even though she calls him 'the young artist' in a very superior manner, Mrs Pat was actually four years younger that Philip. It is true that she wrote and asked her friend to tell her about Edward Burne-Jones' picture at the New Gallery and didn't mention Philip's, which backs up her account that she was closer to the senior Burne-Joneses. However, it was common gossip that she and Philip had been an item and he had spent a lot of money on her, according to Margot Peters' 1984 biography Mrs Pat, buying her furs and diamonds. She then dumped him for Johnston Forbes-Robertson, fellow actor and the model for Love in Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Dante's Dream (1870). Hang on, here's some visual reference for you...

|

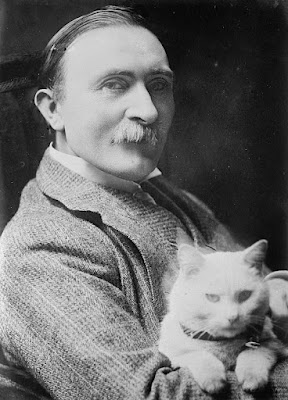

| Philip Burne-Jones (and cat) |

|

| Johnston Forbes-Robertson (1870) |

I'm far too academic to comment that Phil looks like a rubbish Bond Villain and JFB is hotter than York in August, but there you go. Basically, the poem and painting came off as 'boy gets dumped by his girlfriend so he and his mate call her names' but there was something compelling about the image of the vampire woman, climbing over the lifeless body of the man who trusted her, looking triumphant. She appears to have bitten him on the chest, over his heart possibly (a bit obvious, metaphor-wise), and her flimsy nightgown and loose hair makes it appear that she killed him during sex. The Belfast News-Letter called it 'powerful and clever, but cannot be called an agreeable picture' and the Knaresborough Post called it a 'painful but striking allegory'. I was really reminded of this picture by Phil's Dad...

|

| The Depths of the Sea (1887) Edward Burne-Jones |

In many accounts you read about EBJ's painting, the mermaid is certainly not Maria Zambaco (wink, wink), lover of EBJ and general whirlwind of destructive passion. I should clarify here that both father and son are expressing their feelings about their affairs and the women who were their obsessions and we, of course, know that these feelings are arguably nothing to do with the women themselves. Both the mermaid who drags the sailor to the depths of the sea, and the vampire who drains the blood of her lover are seen as wanton, selfish and psychotic. They get what they want, but what of the man? Why won't anyone think of the man! I think the reason both paintings struck such nerves with the critics is because they reflect both the deepest fears of men, to be helpless and betrayed by the one you love, and the utter reversal of the status quo. There are loads of paintings of women being the weaker sex, being seduced and abandoned, dying of broken hearts and the such-like. If I may be presumptuous, I suspect that such images are accepted because the men who looked at them thought I have the power to do that, but I won't. But I could. But I won't. If you turn that around and show men, the critics and main audience of art to be the victims, it would make one wonder if women could be trusted to hold back their lustful, murderous ways (unlikely). Also, maybe you'd like it. We can't have people thinking stuff like that, lawks. My favourite criticism of The Vampire was in the Westminster Gazette which called it a 'disagreeable picture of Mrs Patrick Campbell' in a dirty nightgown and weird light, which was clever but not something you'd want on your wall.

The picture caused such a rumpus that it went on to tour in America, stirring up interest to the point that the customs officials questioned the value that had been put on the painting. They stated that it was too low but not exactly for a flattering reason - 'We estimate Burne-Jones' work not artistically, but commercially' stating that since the scandal it should be worth 'a fortune' of which they wanted 20%. By this tour, in 1902, it was generally assumed that it was a painting of Mrs Pat, even though Philip argued, not very convincingly, that the woman was a professional artists model he had employed in Brussels. Either way, the fame or notoriety of the painting led to Cadbury's producing engravings of the work, due to its 'unusual amount of power and originality' (according to The Globe in January 1902) and Mr W K Vanderbilt purchasing the painting for $18,000. Kipling's 'vampoetry' (as he called it) had become famous alongside the painting and the description of a woman as 'a rag and a bone and a hank of hair' remained in the newspapers as late as 1960. The power of the words and the image led to our second stop on the journey of The Vampire...

|

| Alice Eis and Bert French performing The Vampire Dance |

Bert French and Alice Eis were a dancing duo who had great success in New York. They had been performing an 'Apache Dance' when Bert started looking around for a next sensational subject, to no avail. By magic, a friend sent him a postcard of Philip Burne-Jones' vampiric mistress together with Kipling's poem and suddenly 'The Vampire's Dance' was born.

|

| Alice Eis and Bert French in The Vampire's Dance |

The Ealing Gazette and West Middlesex Observer had an interview with Bert who said that being the Vampire had made Alice so famous she was now unable to go out without a heavy veil as crowds followed her everywhere. London was equally as excited, and Bert complained that he was called on the telephone at all hours from people desperate to meet them. He also revealed he had received many letters praising the moral tone of the work. Let that be a lesson to you - if you dice with a saucy lady, you will come off the worse for it. Interesting, this is arguably not the lesson that Philip and Rudyard had intended people to take from it, but it is no more agreeable. Whereas the original meaning was about the dangers of heartless women, the dance was interpreted more against men who have extra marital affairs who will get their just deserts. Again, the danger is women. Possibly there is some value in claiming that the woman is powerful and is a reflection of the strength of the suffrage movement, but she is destructive and without feelings.

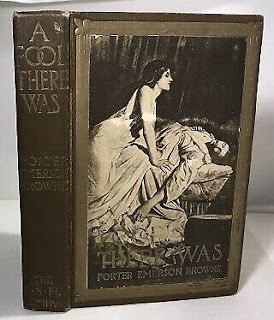

It was described in The London Magazine as 'the ultimate limit in the decadent dancing lately so popular in London.' The dance, the painting and the poem in turn inspired a novel and a play, entitled A Fool There Was (1909) by Porter Emerson Brown, adapted from his novel of the same name which even had the painting on the cover of certain editions...

By the way, should you be tempted to read this pot-boiler, it's free to download from Archive.org. The play of A Fool There Was proved popular, weaving a whole story around the single image. This seems to have led to the 1913 film The Vampire, a story of a man who loved a heartless woman but sees her for what she is after witnessing Alice and Bert doing their Vampire Dance. A little over a year later, the Fox Corporation went one step bigger and better with their epic A Fool There Was (1915), which can be watched on YouTube and is notable as the debut of the incredible Theda Bara...

Sweet heavens above, what is going on there? I want to be her when I grow up so I need to buy more eyeliner. The plot of the movie (spoiler alert) centres around a happy family man and diplomat who travels from America to England by boat, meeting the mysterious vampire woman (or 'Vamp' as it became) on the way. She seduces and ruins him, and it all ends badly for him but she doesn't give a flying fig because she's so very wicked...

|

| Samson and Delilah (c.1887) Solomon J Solomon |

In conclusion, taking the painting first, it seems to have had an interesting fate. For a work that was so modern and successful around the world, it seems to have vanished. I have contacted the Vanderbilt collection to see if they can shine any light on it but if anyone knows where the painting is, please give me a shout. There seems to be no colour images of it, only hand-coloured ones. In many ways, it really wasn't that revolutionary, with clear predecessors in the works of Philip Burne-Jones' father and others like Solomon J Solomon. Solomon's Delilah looks uncannily like Theda Bara almost 30 years later. I find it interesting to see how the meaning of the image shifted quite quickly from blaming the wicked lady for ruining a good man to blaming men for succumbing to temptation. By the time of the movie, the 'Vamp' as she became known, could represent any destructive force, such as gambling or drinking, and the man is to blame for his downfall. Obviously, Theda Bara was extremely attractive and there is a sense that she holds him with her supernatural sexiness and flimsy nightie, but there is a sense that this is a cautionary tale to be on your guard and your ruination is not inevitable, although the better the man, the more targetted for corruption he might become.

There is also a thread to all variations of the vampire tale about the dangers of women discovering how much fun sex is. Taken literally, if a woman is a willing and enthusiastic participant in sex, then it will destroy men. Yes, these women are seen as morally corrupt, but in every version of the tale, the woman is triumphant and moving on to her next victim, with barely a backward glance. In Burne-Jones' painting, she has killed the man and doesn't care. In the 1915 film, Theda Bara crumbles roses in her hands, scattering them over her victim, which would be very much understood as the destruction of romance. Women like her don't want romance, they want your money and your physical ruination, sex without emotion. Forgive the generalisation, but that is traditionally the man's stance, as expressed by Mr 50 Cent in his song In Da Club - 'I'm into havin' sex, I ain't into makin' love', and so if women start encroaching into that where will it stop? They'll be wanting the vote next...

In conclusion, if you are man, especially one on a cruise ship, and you don't want to end up as tragic 'deck noise', I'd avert your eyes from any saucy minxs who look like they want to drain your resources. The women are coming, brace yourself and keep your hand on your sixpence.

_Publicity_Still.jpg)

Another cracker of a post, Kirsty. Again with the 'if it's a man doing it, it's OK, it's 'sowing his wild oats' but if it's a woman, she's a tart (or something worse)'. Would you also include 'La Belle Dame sans Merci' in this category, or what about those tricky water nymphs for Hylas, or the Sirens? There may also be a religious parallel with a woman being the temptress - look at Eve? (Every woman since has had to deal with her treachery, until the Virgin Mary came along - and we've not been allowed to forget it, either).

ReplyDeleteI've always thought it might be fun to be a temptress, but then, I probably wouldn't be able to afford all that eyeliner...

(I won't be able to look at that photo of Philip B-J without thinking he's a 'rubbish Bond Villain!' That made me laugh out loud).

Best wishes

Ellie

Absolutely La Belle Dame and Sirens, together with Merlin and Vivien. I love how it quickly changed from 'Mean girl hurt my mate' to 'Men should really know better'! There would be a lot of maintenance in being a temptress and imagine getting all that off your face every night...

DeleteReally enjoyed your terrific post, particularly since I've started reading a bio of Theda Bara. How odd that no one knows today where 'The Vampire' painting now is (or if it still exists...). I assume The Vampire's Dance you mention is from a 1913 silent titled The Vampire, whose plot, per the IMDB synopsis, sounds pretty stuffy, but the dance, at least in the photo, looks fascinating. Would you have any more info on this film, or if it can be seen online anywhere? Thanks!

ReplyDeleteThe only place I have had luck looking for things like this was on YouTube, which can be limited. I find it odd that there is not more interest as Theda and her work seems so very modern. I really hope someone has the painting and will rediscover it as Philip Burne-Jones' work is not available enough. Thanks for getting in touch!

DeleteI like to think Mrs. Pat bought it in secret to admire or in shame to hide, or a little of both.

DeleteI saw a partial clip of the vampire dance, more a modern ballet dance. it's at the 9min mark of the documentary The Woman With The Hungry Eyes (2006) on youtube.

Delete