I have been considering the role of the muse recently. It is a much contested term these days, with people reclaiming the women who were the inspiration for (predominantly) male artists as people in their own right who existed beyond the canvas (shock, horror!). I remember one of the early post on this blog was discussing the difference between a portrait and a picture and the same could be applied to the role of muse - how much of the role of a muse is absolutely nothing to do with the muse? It is in this frame of mind I read Muse: Uncovering the hidden figures behind art history's masterpieces by Ruth Millington...

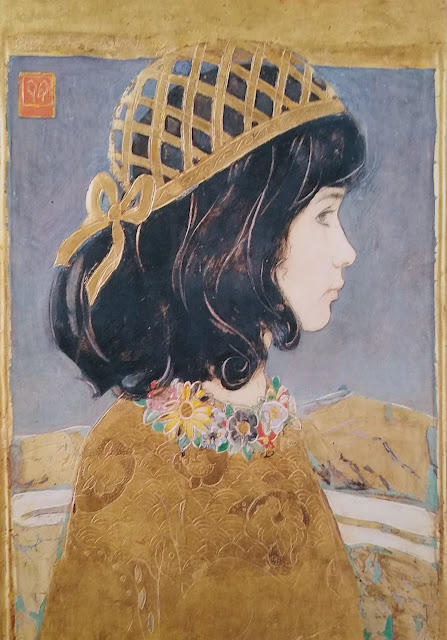

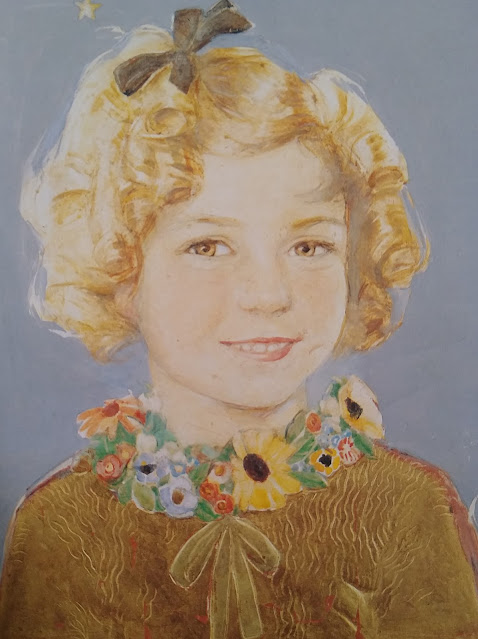

Beautifully illustrated by Dina Razin, Muse explores the many aspects and relationships that make up 'muse-hood'. From family to self to fellow artists of all sorts, together with lovers, situations and causes, what propels one human being to be so inspired by another that they create art around them and what does it tell us about people and the nature of art?

|

| Juan de Pareja (1650) Diego Velazquez |

We begin with the startling story of a seventeenth century slave who became a painter after being freed by one of Spain's most famous artists. Velazquez's enslaved studio assistant, Juan de Pareja inspired this portrait, done the year that Velazquez signed the papers that would eventually free him. There is an uncomfortable tension in viewing this captive man in a formal portrait that seems to elevate him, yet his sleeve is ripped. I would argue that a portrait does not make a muse, but maybe it is the injustice of de Pareja's state that is the inspiration. The subject of the piece is the man, the inspiration is man's condition, the theft of his life in slavery.

|

| The Kiss (1908) Gustav Klimt |

I found the section on Emilie Floge raised a very interesting point about the relationship between artist and muse - do they always have to be lovers? If you accidentally get inspired by someone are you contractually obliged to leap into bed with them (asking for a friend, obviously)? Famously, Emilie and Gustav weren't lovers, just really, really close, yet some of the pictures she inspired were sexual - one title The Kiss was exhibited under in 1908 was The Lovers. Do we judge the artist/muse relationship if they are not constantly having it away? Does it somehow lessen its impact for us? In the case of Picasso and Dora Maar, his 'weeping woman', do we value their relationship more because of the passion that produced the work, despite the emotional trauma that is seeming to be inflicted? Hang on, how do we know that Dora Maar was so very emotional? Is it only because of the art? How much of a muse is the projection of the artist and how much do we as consumers of the byproduct of inspiration take the artist's vision as the truth?

|

| Ophelia (1851-2) John Everett Millais |

The reason Muse attracted me was the inclusion of Elizabeth Siddal, and it raises an interesting question about detachment of persona, as impressed by the artist upon her, from herself. I do wonder if Millais had painted Lizzie roaring with laughter as a happy, sane character then maybe our view of her would be different but somehow the fragrance of doom follows poor Miss Siddal around until we are almost unsurprised to hear that she killed herself. Or didn't, but then that doesn't fit in with the narrative that the artworks of her seem to tell. That's before we start on her own poetry and how we believe that reflected her. I wonder if Sylvia Plath wrote the poetry of Pam Ayres would we still see tragic undertones in 'Oh, I Wish I'd Looked After Me Teeth'?

|

| Christina Olson (1947) Andrew Wyeth |

I really loved the inclusion in Muse of Christina Olson and Andrew Wyeth (Christina's World hangs above my bed as I lovingly carried that poster home all the way from MoMA). The attempts to not only show Christina, who often doesn't face us at all, but looks away far beyond the tradition aversion of the female gaze, but also the limitation of her life due to her disability are powerful. Growing up feeling that my life was very small and confined, I felt an instant affinity with Christina's World and Wyeth's attempt to show disability feels factual yet emotional. Christina's enclosure is as much mental as it is physical - she is held to her home both willingly and without hope of escape. Without knowing that Christina had Charcot-Marie Tooth disease, a degenerative muscle condition, Christina's confinement seems as much as a muse to Wyeth as the woman herself, and that truth of condition, be it physical, mental or societal restriction, reaches people and touches them as it touched Wyeth.

|

| Benefits Supervisor Sleeping (1995) Lucian Freud |

The muses range from the ancient to modern, from Siddal to Grace Jones and all points in between. I think a perfect point is the wondrous Sue Tilley, famous for having a well-deserved kip on Lucian Freud's sofa. The problem with the word 'muse' is that it tends to draw ideas of waft-y little whispers of women who exist only to be painted and possibly have exploitative sex with artists. This book reminds us that not only are the men and women who inspired art real people, often with actual jobs and lives separate from hanging about in a studio with their boobs out, but the term has become reductive and unhelpful. Artists are inspired by many things - not just a pretty face, but also a talent, a spirit, a situation - and much of what we see on the canvas is as much to do with the artist as it is the subject. I would argue that most, if not all, artists use themselves as muse to a greater or lesser extent (as I wrote about here), not just people like Frida Kahlo or Artemesia Gentileschi.

|

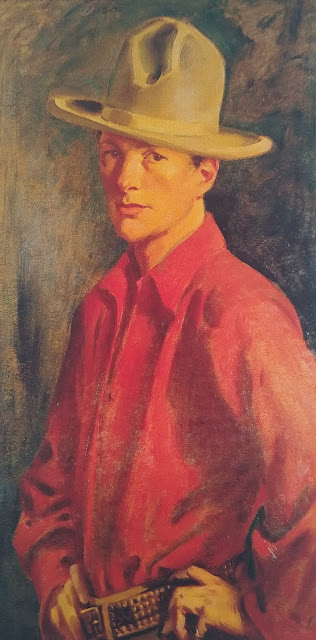

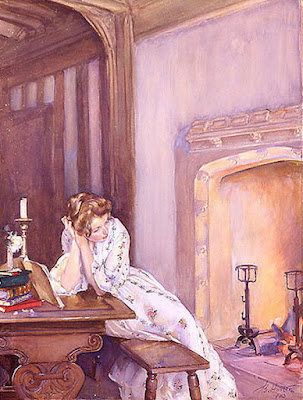

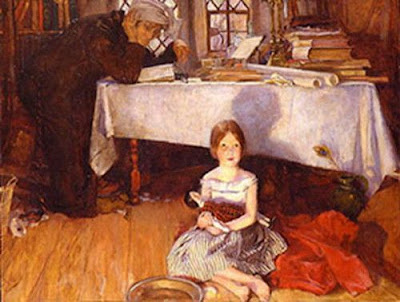

| Fanny Cornforth (1860s) Dante Gabriel Rossetti |

The artist's responsibility towards the muse is nicely summed up on the chapter about David Hockney and Peter Schlesinger, who is famous for being the young man in the pool. Hockney drew Peter reading, reclining and in all manners like Rossetti drew his muses in their off-duty moments. As a muse, are you ever off-duty? Isn't that really the decision of the artist as your muse-iness exists in the mind of the creator. Muse ends on a manifesto for Muses everywhere which includes some rules that should ensure an equal muse-artist relationship. I will joyously uphold the research and acknowledgement of all sorts of muses, and celebrate what the muse brings to the life of the artist, and I think it is helpful to be aware that the 'muse' and the person are quite different. Just as a model who plays a part in a painting should never be assumed to be that person, then portraits of that person should be approached with caution lest we project emotions upon them that might not be there. Just because Rossetti showed Lizzie with her eyes downcast does not mean that she was sad, only that he might have perceived her as thus.

|

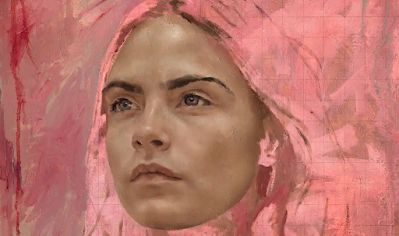

| Cara Delevingne (2016) Jonathan Yeo |

While there was a period of articles decrying the muse, there still are people, okay, mainly women, who are designated muses. What Ruth Millington shows us in Muse is that inspiration comes in forms that are as individual as the people who seek inspiration and there is nothing you can do to stop people being inspired by others. That's a beautiful thing, and yes, an awful lot of it is arguably about fancying someone, but that's not all it is because life is not that basic. What we should stop doing is projecting romance upon unhealthy relationships or expect all inspiration to look the same. I really enjoyed occasionally yelling things at the long suffering Mr Walker, like 'Is there a difference between inspiration, muse and subject?' (yes, of course there is, but where do you draw the line etc etc) and the pen and ink portraits of each of the muses at the beginning of the chapters are perfect and I wish there had been more. It's a great summer read and I thoroughly recommend it.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)