This is a grumpy post, so strap in. It all began by an innocent flick through a 1907 copy of

The Green Room Book looking for info on Ethel Warwick. What I came across left me astonished and extremely depressed. It also led me down a rabbit hole. Let's pause for a moment, and consider the following women - what do Halle Berry, Christina Hendricks, Blake Lively and Taylor Swift all have in common?

|

| Miss Taylor Swift and Cat, real photo |

They, and many other actresses/celebrities/schoolgirls/women have all had to speak out and deny fake nude photographs generated by AI. Taylor Swift's fake nudes recently went viral on X, which doesn't surprise me at all as it is a cursed cesspit, but she is just one of a multitude of victims, albeit one with enough money and influence, if not to stop it, then raise awareness of the crime against her. This is a disgusting modern crime, or at least that was what I thought. Then I met Gertie Millar...

Gertrude Millar was born in February 1879 in West Yorkshire, daughter of an engine fitter and a weaver, employed in the local fabric trade. Gertie, as she became known, was somewhere in the midst of around seven children, but became a child star in the Northern Theatre musical scene, moving from the Manchester theatres down to London by the early 1890s. She toured the provinces with plays, pantomimes and all sorts of variety theatre fare, becoming one of the most popular, most photographed actresses of her generation.

The point about her status as one of the most photographed is relevant, as Gertie seems to have become famous just as the craze for theatrical photograph collecting reached its peak. As I have written about in regards to the gorgeous

Lewis Waller and Audrey Roper's collection, young women especially (but not exclusively) spent a sizable amount of money on the suddenly freely available postcards of their favourite stars, and there was almost a rush to see how many images of certain stars could be produced. I must admit I now have an absolute weakness for buying these images as some of them are beautiful little works of art, but if you were dedicated to people like Gertie or Zena Dare, you would go out of your way to collect as many different photographs as you could. I have noted on the backs of some I have bought, the original owner has written where they saw that actor or actress last, or a friend has sent it to them saying 'I don't think you have this one!' As my daughter says, they seem to be the original Pokemon. You can't just have one Gertie Millar, you have to catch them all!

Gertie was an absolute super star in the modern sense. In 1902, she married composer Lionel Monckton who wrote the scores of many of her musicals. In 1905, a besotted fan shot himself in her house. She was wholesome and beautiful, a little scandalous (she showed her ankles while in pantomime!) but always good fun and professional and the nation loved her.

From what I can gather the photograph publishers would pay an actor or actress for a sitting, then the publisher would have the rights to that image, and it would be up to them to sell as many as they could. The smarter star worked out that in the early 1900s boom in this industry, you should be charging the publisher an absolute premium as they were about to make a small fortune out of your face. The idea of copyrighting your likeness or having control over these promotional images was not yet formed, but one court case changed the way that stars, especially female stars viewed the industry.

If you were a publisher who could make a fortune out of an image of a famous, beautiful young woman, why spend money on new images when you could make your own?

Also, is there any sort of image of a young, beautiful woman that might sell particularly well? What might tempt the untapped market of men to buy images of actresses?

Hmmm, let me think...

It all started quite innocently, with the slight changing of one image to another. Gertie Millar is seen as possibly Miss Muffet, shaking her finger at a naughty spider. It seems to be one of a series (as they often are, all products of the same photo-shoot, making as much money from one session) and in other images Gertie is either dancing or being afraid (although with a smile) but the one we need here is where she is shaking her finger. It is what is described as a 'novelty image,' an impossible, amusing photograph, altered to be humorous. This might have been to do with one of her pantomimes but might just have been a cute image. There are any number of things like this - women popping from crackers...

|

| It's either a very large cracker or a very small actress... |

...emerging from Easter Eggs...

|

| It would have been embarrassing if we had boiled Gabrielle Ray... |

Maybe you just want your name written in actresses' faces?

As you can see, things moved swiftly from images of a person, or of a scene/character in a play to more unique, unusual images. However, what if the images were not what you, the subject, wanted and felt that were detrimental to how you were seen by the public? This is where Gertie Millar came in. Remember the picture of her with the spider? How about this one...?

In 1905, Gertie noticed that there were images circulating that she had not been aware of. Starting with the image of her with the baby, she was sent other images that she had not even sat for. While she did not take great exception to the image with the baby (it is offensive because of the connotation and the way it was subsequently spoken about, but also it is just Gertie shaking her finger at a small child rather than a spider), there were others where Gertie's head had been put on the body of another woman, and you will be unsurprised to hear that woman was rather flimsily dressed. They all were released by R Dunn and Co, publishers at 63 Barbican in London. Ralph Dunn had made a business in the production of all sorts of photographic images, obviously moving into the celebrity postcards because of the money to be made, and many of the more novelty ones I found were registered to them, so they were obviously skilled at image manipulation, or rather weren't afraid to create an image when one was needed. However, Gertie felt that Dunn had done her reputational damage and so she sued him.

There was a short paragraph in The Green Room from 1907, under the title "FAKED" PHOTOGRAPHS which stated:

'Miss Gertie Millar aired a real grievance in the Court of Chancery in June last, when counsel appeared on her behalf, and asked for an injunction to restrain Messrs. R. Dunn and Co. from publishing postcards on the back of which appeared photographs representing her in a nightdress, and in other different costumes none too abundant.'

Obviously, the term 'none too abundant' caught my eye as that really could only mean one thing, they had made fake images of her with her kit off. Gertie, appearing as Mrs Lionel Monckton, began the case in April of 1906 but had to wait until the beginning of 1907 to have it heard in court. The press coverage at the start should have given us a warning of what was to follow, as the Bristol Magpie set the tone in a short piece in April 1906:

'Gertie Millar recently tried to restrain a certain firm from publishing picture post cards, representing her in a night dress - not of course that the actress wanted to be exhibited without the gown in question, but because she thought the costume a bit too light and airy, of course it was very naughty of Messrs Dunn to do it but it is to be hoped that Gertie's garment will in future find less display on public postcards, such a sight should only be reserved for the pillow and the bolster.'

Let's start with exactly why this bothers me so much - the use of 'naughty' and the hint that the night dress was Gertie's, that she had accidentally posed in it and now was trying to take back the image, or that she would be better off without it. All of that set the stage (as it were) for a court case that not only argued that as a public figure, Gertie's body was public property, but also a very loud undertone that if women didn't want to be seen in very little clothing, then they shouldn't go around being naked under their clothes. It's the same reasoning that reduces the seriousness of when a girl's nude photograph is passed around.

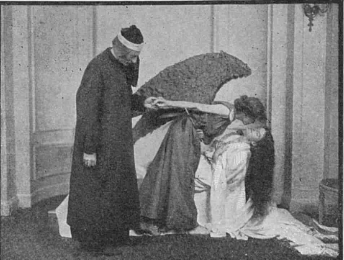

|

| Exhibit A |

Viv Gardner included the images in the marvellous chapter 'Defending the Body, Defending the Self' of

Stage Women 1900-50 but I bought my copies of various faked images off eBay for around £1, which is sobering. In the April hearing in 1906 with Mr Justice Warrington presiding, Mr Whateley (on behalf of Gertie) applied of an injunction to restrain R. Dunn & Co from issuing the postcards bearing the alleged images of Gertie in a nightdress, as Circe (wearing very little) and emerging from an eggshell. Whateley stated that the photographs had been created by placing Gertie's head on another woman's body. Stunningly, Ralph Dunn agreed that yes, that was exactly what they had done and said he wouldn't make any more. That was easy, wasn't it? Whateley said that Gertie would be seeking damages for them making the fake pictures. That's when the trouble started.

|

| Queen Victoria Receiving the News of her Accession (1880) Henry Tanworth Wells |

The Portsmouth Evening News reported on the trial that started in January 1907 under Justice Darling, a frankly atrocious human being and obviously ironically named. Gertie's contention was that by showing her semi-nude, or even in her night attire, it would lead the public to think she was 'an indelicate, immodest and vulgar woman.' She particularly objected to the one in her nightdress and the one where she was emerging from an egg as they were 'very vulgar, and she also objected to them because they were not pretty.' Now, we come to the problem as the newspaper reported that the last statement received laughter. In fact, the whole of the court case was played like a musical hall skit with Justice Darling assuming himself to be the star comic turn. When Gertie was cross-examined, it was put to her that she had been in a play where she had sung a song about a bathing suit and in The Orchid where she sang a song about pyjamas, therefore why would she object to being pictured in said garments. Furthermore, because she objected to the nightdress, the defendant's council asked if Gertie knew of a painting depicting Queen Victoria receiving an Archbishop and the Lord Chamberlain in her nightdress on the night she ascended to the throne? Gertie replied 'Oh, that was before my time.' (laughter)

|

| Gertie in The New Aladdin |

Dunn's main defence was that actresses wore nightdresses on the stage, even Lady Macbeth and Juliet wore night gowns in the plays, even though Gertie pointed out she had never done it herself. It was pointed out that Gertie was currently appearing in the pantomime The New Aladdin playing the Principal Boy in knee breeches and high boots. She had also appeared as a costermonger, dressed as a man. What is the problem of her being pictured in more feminine attire? She had also actually appeared with an egg for The Orchid in April 1905...

In the contested image (I think it is this one I pinched from eBay), Gertie is seen crawling from an egg...

You can see 'R. Dunn' written on the bottom left side even though the image had been taken from a photograph by Bassano. To our modern eyes, Gertie is adequately dressed in both of these images by Dunn - the image of her as Circe or a Sea Maiden, depending on who is talking about it, is slightly more risque and hard to find, but she is still covered up with gauze - but as Gertie summed up, she felt she should have the right to choose what way she should be presented to the public in photographs. This is not a painting, this is a photograph which people believed, especially in this period. No, the public are not going to believe she exploded from a cracker or somehow cloned her face into the name ETHEL, but when it seems a straightforward image of the woman crawling from a giant prop egg, or holding a candle, then it seems like a real image that Gertie posed for and approved.

|

| The Somnambulist (1871) John Everett Millais |

The questioning was relentless - when shown other images of women crawling from Easter eggs, Gertie said she knew of them - they were eggs with beauties inside. The defending counsel swiftly said 'but you are not one of them?' and Gertie replied 'No, I am not among the beauties' (much laughter). Gertie appeared in furs at the court, a brown on the first day and an ermine on the second, which was noted. It was asked if she knew that her postcards sold for 2 pennies, which she knew. She was asked if she knew that Dunn sold his made-up cards for a penny, which she did not know. She was asked if she would appear in a nightdress on stage, in for example in the opera La Sonnabula or as Lady Macbeth and Gertie said she probably would if the role required it. When asked what she wanted, Gertie simply said that she wanted people to know that it wasn't her in the postcards. She was asked if she wanted compensation, she said that was for the jury to decide. The woman in furs had said she not only wanted to stop the man making money from his postcards but also refused to let her postcards be a penny, an affordable sum.

|

| Gertie Millar, well, part of her... |

The argument became one of imaginary rings of big publishers, all banding together to run the little man out of the business because he had dared to publish photographs at an affordable price. Despite the reiteration that Gertie just wanted them to not fake her image, Dunn said he was only giving the public what they wanted. The jury found him innocent in only 10 minutes.

However sneering the papers were before the verdict, they soon changed their tune because Gertie was not wrong to believe she was valued by her public. She published a very dignified letter in the newspapers on 4th February, a few days after the verdict, to thank the people who had reached out to her and conceded she would not be appealing the verdict. The jury had told her she was wrong to bring the action, but the public had told her she was right to feel defamed by a fictitious photograph. I particularly enjoyed G K Chesterton's rebuttal of the whole case in the Illustrated London News where he rightly points out all kinds of fictitious images can be created in paintings, but photography is believed to be true and real. When Gertie said that people seeing the image of her wrapped in gauze by a riverbank or appearing in her nightie would think it was true. Chesterton went further and said the argumentative nature of the case was ridiculous when the crime was openly admitted to - if a coal-heaver was assaulted, he would not be expected to argue the ethics of assault in court. Even the Law Journal got involved, criticising the behaviour of Justice Darling. Gertie's counsel, Mr Foote KC did not stand a chance against the main-character-energy of that judge, going out of his way to state outright that Gertie was no better than she ought to be. The way he tried to imply she thought herself better than the Queen made a mockery of her as everyone knew she was just a working-class lass who sang funny songs for a living, sometimes in trousers where you can clearly see she has two legs.

Within the month Lionel Monckton had written Gertie a new song to perform entitled 'My Photographic Girl' about the whole affair. Good for them. However, that was not the end of the affair, and, for a moment, the can was open and the worms were everywhere. Look what else I found on eBay...

Actresses flooded to the newspapers with their own stories in support of Gertie. Miss Marie Corelli was refused an injunction against a photographic publisher who faked some of her images. Miss Denise Orme's image was altered, her evening dress painted out and a see-through gown put in its place. Edna May had found countless images of herself crawling from seashells and eggs and in a variety of costumes and she had to complain to the publishers, although she feared millions of copies were already in circulation. Constance Collier said she had to be careful, and her own publishers were vigilant, but the verdict frightened her. Camille Clifford quite rightly saw there was no limit of what could be done with her head on another's shoulders. Olive May thought it was potentially ruinous for a young actress who would not be hired if she was thought to be the sort who posed in the nude. Anonymous actresses reported knowing their images were being faked but not wanting to be the sort of girl who causes trouble as that too would ruin your career. All sounds very familiar, doesn't it? As the image of Carrie Moore above shows, the practice was widespread, and the actresses all wisely feared but didn't explicitly say 'where will it end?' and now we know. Tellingly, I have not found any reports of male performers being faked in this way. Whilst I don't doubt these days both sexes are probably victims of those who wish to fake images, I'm willing to bet the majority (by probably a mile) are still women.

Truth magazine published their own exasperation in the verdict, and added a poem which sums up the situation we are in now, so I will finish with that:

I thought it hard her face they matched

With form suggesting too much leg;

I thought it hard they showed her hatched

Just lately from an Easter Egg.

I thought it hard they stuck her head

Upon a trunk in nightdress clad;

And yet - so judge and jury said -

No legal remedy she had.

If that's the law, I'm much afraid

That I, one day, my face will find

On someone else's frame displayed,

Clad only in a - never mind -

Or even worse in nothing dight

(For where the limit can you draw?)

And yet I'll not have any right

To stop their game - if that's the Law.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_01_Crisco_edit.jpg)