You know how much I like a delicious tragedy. I'm always drawn to people who have a life of unfortunate events, then die in a swift and unexpected manner, better still if their entire family is peppered with calamity. Imaginethen my delight when I met the beautiful Eleanor Butcher...

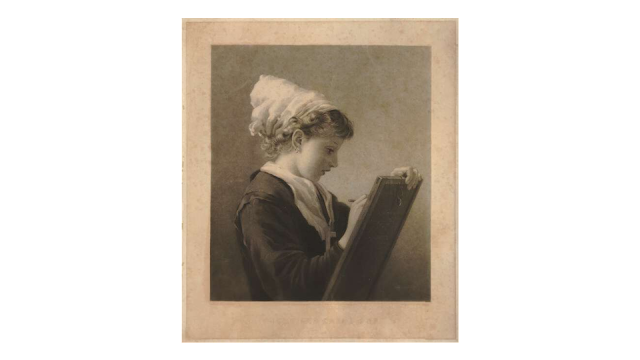

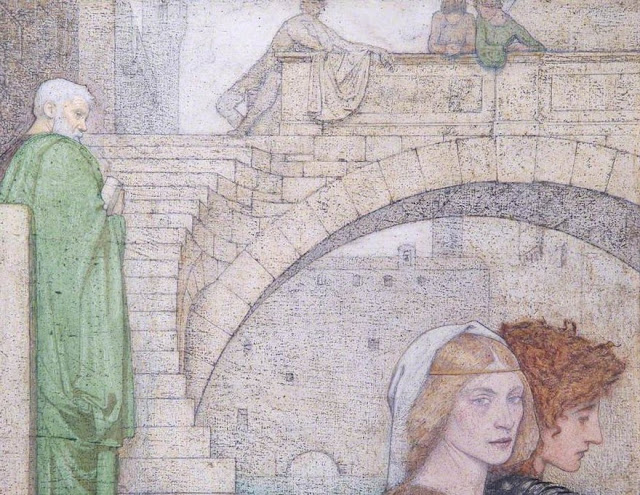

As it turned out, I already knew Miss Butcher, and have used her image many times in the past because she posed for Beatrice in this painting by Henry Holiday...

|

| Dante and Beatrice (1883) Henry Holiday |

Beside the river Arno in Florence, Beatrice, in white, takes a stroll with her bestie, Monna Vanna, and a maid, watched by Dante. In those flowing white robes is Eleanor, out for a stroll with Milly Hughes and Kitty Lushington. At first, I wondered if Milly was Emily Hughes, daughter of artist Arthur Hughes, but apparently Milly was the daughter of an old friend of Holiday. Kitty Lushington is marvellously famous, and there is no doubt who she is...

|

| The lovely Kitty Lushington |

I could write an entire post on the lovely Kitty, who was the blueprint for Mrs Dalloway and plunged to her death over a banister and down the stairs (not by accident, according to Virginia Woolf). However, this is Eleanor's post, so Kitty's tragedies will have to wait.

|

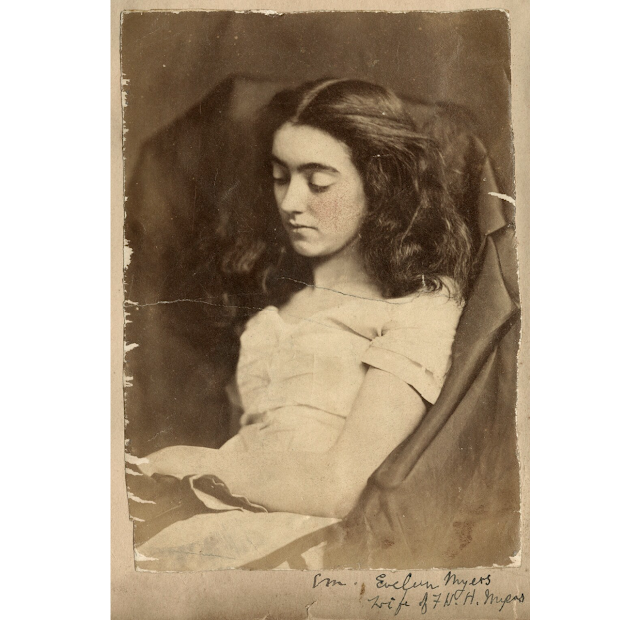

| Eleanor Butcher (unknown photographer) |

Eleanor Louisa Gertrude Butcher was born in April 1860. Her parents, Mary and Samuel were Irish and had homes in both London and Ireland after Samuel became Rector of Ballymoney. The family moved their Irish residence to Ardbraccan House when Samuel became the Bishop of Meath in 1866. Eleanor was the second youngest, after Elizabeth (1849-1908), Samuel (1850-1910), John George (1853-1935), Margaret Frances (Fanny) (1854-1934), and Augusta (1856-1899). Eleanor was followed by Clara in 1861. I'm not entirely sure what became of Clara as I can find her until the end of the century, as, like her sisters, she was musically accomplished and acted as bridesmaid to society friends. After that, it seems we don't talk about Clara. If I hadn't seen her in the 1881 census, I would have imagined she was fictional, but there she is. I don't think she came to a particularly tragic end so let's move on.

Eleanor's family was exceptionally well connected and her siblings furthered that through work and marriage. Elizabeth married Thomas Spring-Rice, the 2nd Baron Montegal of Brandon in 1875. If the name Spring-Rice is familiar, it's because of things like this...

|

| Mary Spring-Rice O'Brien (1867) Julia Margaret Cameron |

The Spring-Rice family were in with the Freshwater crowd and knew Tennyson, so Tennyson went to visit the Elizabeth at her new home after her marriage, as Hallam wrote home to his mother - "they were most affectionate...Papa read Maud which gave great pleasure, and Eleanor Butcher (the babe) was found on a rock by herself in the Shannon. She is a wild, simple young child.All the three Miss Butchers are each 'eine natur' as Goethe says." As Elizabeth married Montegal in 1875, the wild child discovered by Hallam in the Shannon must have been a teenager and already knew how to make an impression, obviously.

|

| John George Butcher (1926) Lafayette |

As for the rest of her siblings, John became MP for York and was elevated to the House of Lords in 1923. He balanced being a keen sportsman with being anti-vivisection, which is an interesting combination seeing as he was of the class that always involves killing something small and squeaky. Both Fanny and Augusta also married well, and we'll come to Augusta in a bit, but as you can imagine, when it came to marriage, the beautiful Eleanor was a popular girl. Lucky for us, she took her time and weighed up her choices which caused her to be written about in quite a few people's diaries. However, in 1876 something tragic occurred which could have ruined her chances completely. Her father committed suicide.

Samuel Butcher had been the Bishop of Meath for a decade, and his family was established into English society with great success. I get the impression that Samuel spent a lot of time at Ardbraccan as that is where he had been convalescing in 1876 from bronchitis which had been lingering for a few weeks, however it was felt he was recovering. On Saturday 29th July, he rose earlier than usual and went to his study, where he locked the door. They had to break the door down, discovering that he had cut his throat with a razor. In his hand was a scrap of paper containing a single word, 'mad'. It was concluded that he had been temporarily insane, caused by his illness and in light of his life's work, a remarkably modern view was taken, at which I must admit I was pleasantly surprised. There were some pretty florid descriptions of his funeral at Ardbraccan, including a complete appraisal of his coffin (shell and lead inside, polished oak outside) and visions of the 'almost impassible profusion of summer foliage' on the way to the graveside. My goodness, the Victorians loved a funeral. There seems no stigma, at least publicly about his death, and in comparison to the alleged panic around Eizabeth Siddal's death, it all seems sympathetic and sad.

|

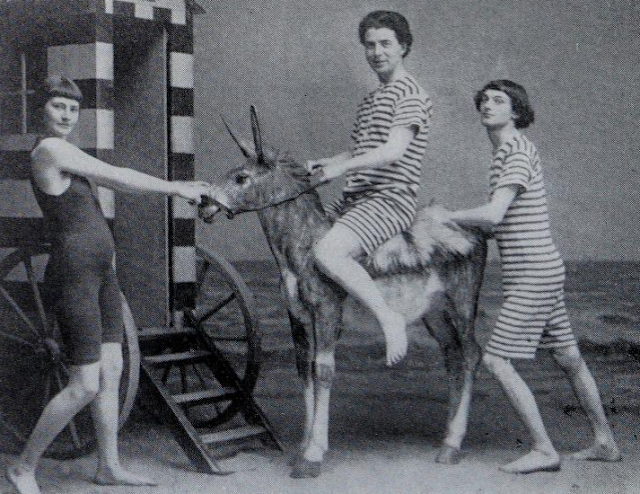

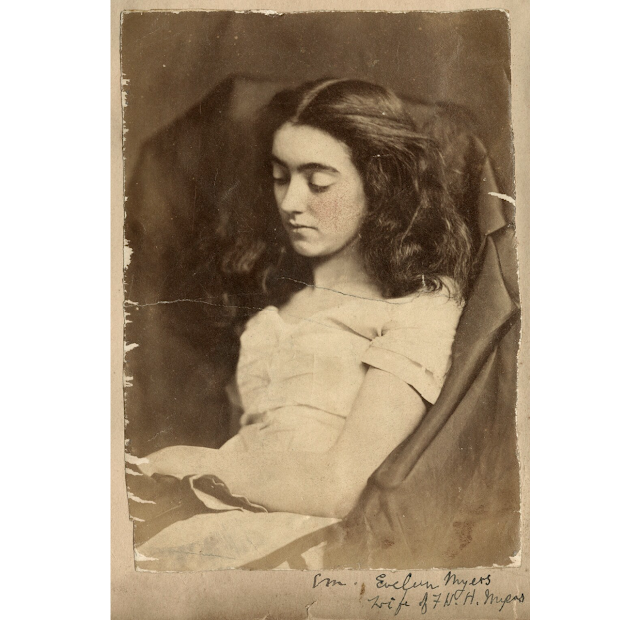

| Augusta, Fanny and Eleanor (1880s) Eveleen Tennant Myers |

Despite the tragedy, the three eligible Butcher girls, Fanny, Augusta and Eleanor were launched on the marriage market in the 1880s. William Rothenstein remembered them in his memoir as being "three enchanting ladies, spirited, enlightening and vivacious talkers." Eleanor especially "made life seem more worth living; to have her friendship...was, I felt, a privilege." The brothers, Samuel and John, had gone to Trinity College, Cambridge and the girls had gone to enjoy the society there. Fanny had befriended Ida Darwin, daughter-in-law of Charles Darwin, and sister-in-law of George Darwin, who was looking for a wife. There was quite a bit of interest from their clique when after on a few meetings over two years, Fanny became engaged to George Prothero. A family friend questioned her decision: "I asked how she could know her own mind so instantly. She said whenever anyone else came near her somehow he never seemed as nice as Mr Prothero, and though not the least unhappy about it, she knew from that that he was her standard. Everybody including me thinks her very fortunate."

Fanny and Eleanor were extremely close, and their friends worried that Eleanor would be lonely. Or possibly they were worried that Eleanor would not be lonely, if you know what I mean, as it didn't take long for several names to be attached to hers. Eleanor was very much admired for her looks - "She is lovelier than ever, in such an exquisite highbred way, which throws such a bar-maid beauty as Mrs Fred Myers completely in the shade..."

Oh good Lord, well that's appalling. So, Mrs Fred Myers was actually Eveleen Tennant, photographer and bar-maid beauty - I assumed Bet Lynch and leopard print, but was sadly disappointed.

|

| Eveleen being not very barmaid-y, 1870s (unknown photographer) |

Eveleen married Frederick Myers in March 1880, but before (and to be honest afterwards) he was a bit of a one for the ladies. In 1878, he set his sights on Eleanor but, as would become apparent, Eleanor was a bit of a procrastinator when it came to men, which I think made everyone nervous. Possibly it showed good taste. If Fred was still interested in Eleanor, it didn't stop Eveleen and Eleanor from being friends as the group shot of the sisters is labelled "Taken by their friend Mrs Frederic [sic] Myers" in Lady Jebb's memoirs, and also didn't stop Eveleen taking this exquisite image of Eleanor in the early 1890s...

|

| Eleanor Butcher (early 1890s) Eveleen Tennant Myers |

When it came to Fred Myers, the women looked on with some concern - "He is very companionable and with an insidious nature. Fanny said her mother is so afraid of him that she believes if there were no other way of keeping Eleanor, another sister, from his influence, she would leave London altogether." However, any fancy she had for Fred soon waned and she moved on to the next suitor...

|

| Gerald Balfour (1890s) Lord Battersea |

Gerald Balfour was the brother of Arthur, Prime Minister and member of the Souls. Like Fred Myers, Gerald was deeply involved in spiritualism and served as President for the Society of Psychical Research. It was noticed that Gerald was attracted to Eleanor, and why not, as she was described as having "a most attractive face, which fastens your eyes and fascinates you" (yes, but could she pull a pint?). Anyway, a family friend noted in 1879 that she was inclined to think Gerald had had an effect on Eleanor as "she is more silent and shy with him than with others, a good sign. He makes no effort to conceal the attraction she has for him, talks to her at dinner parties all the evening, never speaks to Augusta, nor does anything but openly show his intentions." Firstly, poor Augusta, but possibly she had a lucky escape because his courting seemed to involve endless conversation about political economy. Ladies love political economy. Sadly, the romance did not last long, as he found that she was full of fun and humour, which is absolutely disgusting in a woman.

|

| Walter Leaf (1891) Henry Herschel Hay Cameron |

Unfortunately, Eleanor actually quite like Gerald and rebutted the advances of Walter Leaf and George Darwin because she was in love with him. Eleanor actively started to pursue Gerald (with all her fun and humour, the horror) and gatecrashed boating parties where he was supposed to be, but to no avail. Gerald swore he would never marry, then in 1887 married the (no doubt rich) daughter of the former Viceroy of India. Although Walter Leaf and George Darwin continued to court Eleanor into the 1880s, neither seemed to like her much. George admitted that "married to a wife so devoted to excitement he should only have been miserable" leaving a friend to conclude "She is selfish, there is no doubt; yet she is the cleverest girl I know in England...[George] says it is her self-consciousness that stands in the way, nothing repels so much."

|

| Lewis Nettleship (c.1870s) Unknown Photographer |

By 1883, Eleanor decided that she should be looking to get married, as a friend said "she is getting to a suitable time of life, twenty-eight." I was again surprised that a woman was allowed to reach that sort of advanced age without being completely written off but I think if you have good connections and a fair amount of money, any age is a good age to get married in the eyes of society. Eleanor befriended Jane Ellen Harrison, suffragist and linguist, and the pair holidayed together with other friends at Robin Hood's Bay including Alfred and Violet Hunt, the imaginative biographer of Elizabeth Siddal, and Lewis Nettleship, described in one of Jane Ellen Harrison's biographies as "a sad aspirant for Eleanor's affection". Nettleship died in 1892 from exposure after getting trapped on Mont Blanc, which is a marvellous effort on the tragic front.

|

| Eleanor Butcher (1890s) Charles W Furse |

Eventually, Eleanor met her match. Charles Wellington Furse was also a son of the church, in his case the Archdeacon of Westminster. Charles was a talented artist, attending both the Slade and Julian's in Paris, before setting up his studio in Tite Street, alongside such people as Whistler and Singer Sargent, whom he greatly admired. Eleanor became a frequenter of not only his studio but also others. Devon Cox's wonderful book The Street of Wonderful Possibilities tells of how Eleanor would burst into George Jacomb-Hood's studio and demand tea and toast, staying until the early hours of the morning.

|

| Private View at the New Gallery: The Crush in the Central Hall from The Graphic, May 1893 |

Around this time, Eleanor posed for Charles Edward Hallé and the subsequent portrait was exhibited at the New Gallery in May 1893, possibly alongside a portrait of Margaret Burne-Jones with which it had shared studio space. The exhibition was extremely busy and the Richmond and Ripon Chronicle had kind words for the portrait, declaring it "most striking". Somewhat less friendly was the Yorkshire Post who declared "Anything more wooden...can hardly be imagined and its presence on the wall is scarcely to be excused by his official connection with the gallery." Well, ouch.

|

| Portrait of a Lady (Eleanor Butcher) (1894) Charles Furse |

A much better reception came for Charles's portrait of Eleanor which appeared in Volume 1 of The Yellow Book in 1894. Aubrey Beardsley judged it to be "A1". Eleanor and Charles's engagement was announced on 24th April, coincidentally in the same edition of the Westminster Gazette as the announcement of old suitor Walter Leaf's engagement to Charlotte Symonds. Their wedding was set for May, a month later, which might be a bit of a red flag. Charles's health was somewhat delicate as he had been suffering from tuberculosis since his days at the Slade, but when it came to it, Eleanor went first.

Exactly how she died is a little muddled. In Jane Ellen Harrison's biographies, it is inferred that Eleanor went into a nursing home for a minor operation, on Jane's encouragement. She was recovering well but then died suddenly after an afternoon of receiving visitors, which is fairly dramatic. Another account states that she had been suffering from TB and this had weakened her to the point that she dropped dead, after a short illness. Whatever was the case, her funeral was a lavish affair in the presence of a large group of her family and friends. Her coffin was completely smothered in white flowers sent by those who loved her, including Florence Balcombe (Mrs Bram Stoker) and Anne Thackeray Ritchie. Charles did not outlive her for long and died a decade later of TB, after marrying the younger sister of Charlotte Symonds, Katherine in 1900.

The letters of Lady Jebb, which is a wonderfully gossip-y read contains this note from 1895 - "Did I tell you that Augusta Butcher is to be married at Easter? She has accepted a Mr Crawley, a great friend of Frank Darwin's, a barrister, and apparently a very nice man. All her friends are delighted, for her life was very lonely after Eleanor's death."

Wouldn't it be a relief to finish here? Sorry.

On a blissfully hot August afternoon in 1899, Charles and Augusta Crawley visited one of Charles's sisters in Bryngwyn, near Raglan and decided to leave their two young children with a nurse and go for a boat ride down the Wye. The elderly boatman who accompanied them accidentally struck the boat on some underwater debris, sinking it. In the resultant panic, Augusta, Charles and his sister drowned. As a footnote suggests in Lady Jebb's correspondence, death did seem to stalk the Butchers, which makes the comment that Eleanor made life seem more worth living seem rather ironic. However, the brightness of Eleanor Butcher, her fun and humour and demands of toast and tea, does seem to have provided such vivid light to others. She illuminated the memories of others long after she had gone.