We have reached the penultimate Stabvent entry, hasn't time flown? Presents have been wrapped and I have a list with which to do battle with the supermarket, so onwards with today's tragic, messy death...

|

| Scene at Holyrood, 1566: Death of Rizzio (1855) William Borthwick Johnstone |

Here we have a jolly scene - David Rizzio and Mary, Queen of Scots are having a bit of a chat, but just outside the room, lots of chaps are waiting to spring a splendid surprise party. One of the chaps is so overcome with excitement that he is having a little lie down to recover. How jolly! Okay, I suspect not all is going well here and those chaps in the hallway are not concealing a lovely cake after all...

|

| The Murder of Rizzio (1787) John Opie |

There we go. Knives out and away with the stabbing while poor pregnant Mary, QoS, tries to intervene. This is a brilliant painting, full of movement and drama, with Rizzio on the floor about to meet his doom. So, what happened to cause this calamity?

|

| Mary, Queen of Scots and David Rizzio (c.1870) John Rogers Herbert |

Mary, Queen of Scots is one of those historical figures who had a lot of bad things happen to her and then she made a lot of dodgy choices. More than likely one begat the other, but whenever I read about her, I feel both horribly sad for her and really cross with her. Part of the problem was that she was only six days old when she became Queen of Scotland, which meant that other people had to rule in her stead as Regents until she was old enough. That sort of thing leads all sorts of people to believe that they can rule instead of you, and that you are not capable of being a queen on your own. She also got married off when she was 6 to a French Dolphin, excuse me, the Dauphin of France and so ended up Queen of both France and Scotland, although not really queen of either, if you know what I mean. As the only surviving legitimate heir of James V of Scotland, she was the only person who should have been in charge - does that remind you of anyone?

|

| John Dee Performing an Experiment before Elizabeth I (c.1880s) Henry Gillard Glindoni |

Contemporaries that would become rivals due to the machinations of Elizabeth's court, Elizabeth and Mary should have been allies because one thing they both needed was a friend who was not after anything and completely understood the pressures of being a Queen. Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately) Elizabeth had no mother to marry her off, so really was without family ties when she ascended to the throne, and she was an adult. Mary was not so lucky. She was widowed before she was 18, the same year her mother died and was shoved back into Scotland, a country that had been managing without her rule, thank you very much. She then got married off to her half-cousin Lord Darnley, who was not very pleasant. He wanted to be King rather than just the husband of the Queen - excuse the generalisation, but in history, I am struck by how badly men who marry Queens seem to cope with that. I suspect the Queen just marries the wrong sort of bloke, but I am always struck by the struggle of these chaps with not being ultimately in charge. I know, I know, #NotAllQueensHusbands, but it does seem an awful lot of them. Anyway, into this rather tense marriage came David Rizzio...

|

| David Rizzio (1600s) Unknown Artist |

This painting from the Royal Collection is allegedly David Rizzio, although contemporary accounts called him a short, ugly hunchback. Now, come on, of course they did which probably means he was tall and exceptionally hot, and also even if he was ugly, doesn't mean he wasn't excellent company and very charismatic. Either way, he wasn't Mary, Queen of Scot's irritating husband and as far as we known, Rizzio didn't actually want very much from Mary, which made a damn change in the poor woman's life. Rizzio was looking for a job, starting in Turin, then moving on to the court of the Duke of Savoy and then to Nice but he wasn't getting anywhere. He travelled from France to Scotland in search of work but there was nothing for him there, however he found that Mary needed a bass singer to join her musicians she had brought home with her from France. Having a lovely voice, he got the job. Not only that, he was pleasant company, educated and obliging and so he became Mary's private secretary.

|

| 'David Rizzio Playing for the Queen' from Britannia and Eve, 1935 |

Mary relied on Rizzio to keep her company and possibly act as a buffer between her and her awful husband and his crew. This led to rumours that the pair were conducting an affair, compounded by the announcement that Mary was pregnant. The appalling Darnley grew so jealous that only one thing was to be done. Poor Rizzio's days were numbered.

|

Conspiritors arranging the Murder of Rizzio (no date) William Lindsay Windus

On the evening of 9th March 1566, Rizzio, and the pregnant Queen were having dinner when there was a kerfuffle in the outer room and a group of Darnley's awful friends stormed in, demanding that Rizzio come with them. For obvious reasons, Rizzio was not keen and the Queen stood between him and the motley crew. Various threats were made to the Queen and then they grabbed Rizzio and stabbed him around 57 times. Darnley was conspicuous by his absence but allegedly, the last blow was with Darnley's dagger before Rizzio was thrown down the stairs. There is a plaque at the bottom of the stairs in Holyrood where Rizzio died and a stain on the floorboards - again, you have to put your back into scrubbing up stuff or this is what happens.

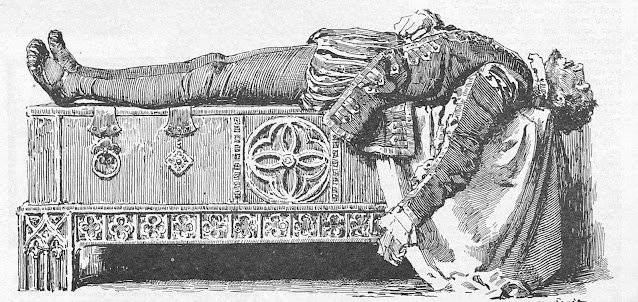

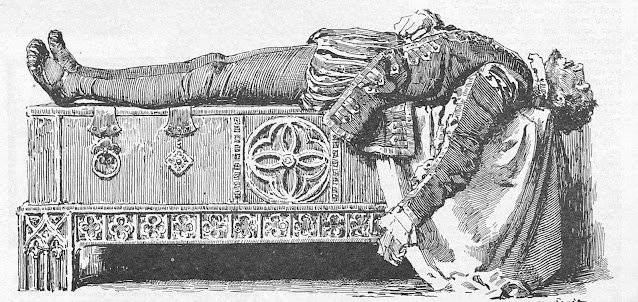

| | Rizzio, laid out on a wooden chest in the Porter's Lodge from Britannia and Eve, 1935 |

|

Although Darnley claimed to have no part in the actual murder of Rizzio, his big, shiny dagger sticking out of the poor musician must have made Mary realise who was behind it all. Also, not being the brightest of chaps, Darnley apparently had a written bond with his co-conspirators saying exactly what they were about to do. For goodness sake. As for Mary, she gave birth to her son James, who would end up as James I of England and James VI of Scotland, finally doing what his mother had not managed, ruling two countries. Mary never trusted Darnley again (if she trusted him before, which seems doubtful) and wasn't exactly broken-hearted when he died accidentally in an explosion which left him some distance away, stabbed. A very unique sort of explosion then... She went on to marry one of the apparent murderers of her husband, three months later.

The murder of Rizzio marked a turning point for Mary which epitomises the problem with Mary, Queen of Scots. Things happen around her and she becomes the victim of them, never quite managing to get in control or pull rank. It is easy to compare her to Elizabeth I and see how one woman seemingly got it right and one got it horribly wrong, but Mary had so many more hurdles and problems thrown in her way and she made terrible decision from which she was not allowed back. Elizabeth chose not to marry, which turned out to be a wise decision in many ways, but for Mary, that decision was made for her, at least twice. Had the French Dolphin lived longer, she might have been a splendid Queen of France. Had Darnley not been a baggage, she might have been a marvellous Queen of Scotland. Had she made an ally of Elizabeth I, she might have become Queen of England after Elizabeth, just as her son became King. However, she had terrible advisers, horrible situations thrust upon her and pitiful choices. Then she died. As for Rizzio, he was merely collateral damage in Mary's chaotic life. I'm guessing, taking Darnley's character into consideration, if it hadn't been Rizzio, someone else would have ended up stabbed. What a complete pickle, but that's history for you.

I'll see you tomorrow for the last Stab of the season...

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(14753085992).jpg)