I had only a faint sketch of my late sister, Sophia by her

husband, the artist Philip Archer. His art, though

extremely accomplished, had no charm for me, much like the man himself. That one

sketch though was pressed upon me after her funeral. He had wrapped it in black

tissue, a farewell present as the frost and dirt still clung to my boots. He expected never to see me again and so I

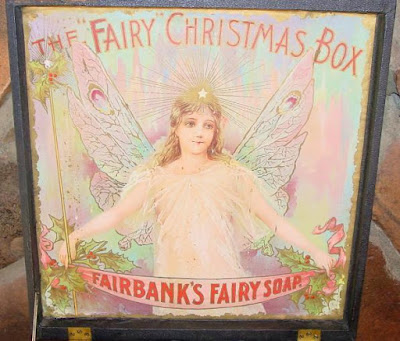

was to be dismissed with this half-work of her, dressed as an angel, her arms

outstretched in a darkened room. He kept the oil, finished but never shown. I

will say that in his defense, he never showed that last painting nor sold it.

It hung on his landing, a curtain carelessly pulled back next to it so that it was

partly obscured. My angel-sister was all but forgotten by Philip Archer until the

third Sunday in December. That’s when I received a note. It was brief, heavy-inked

letters spelling out two words.

SHE MOVED.

I did not relish the trip to London, so comfortable

had I become in my rooms in Oxford. I

had my work, my books, my little cat. His letter had disturbed me, and had been swiftly followed by a note by

a ‘Dr Carstairs’, a friend of Philip’s, which did nothing to ease my mind.

‘Miss Davis,’

it began, ‘Forgive the imposition upon

your time by one who is not known to you but I believe you will have received a

letter from my friend, Philip Archer. I do not need

to tell you what a shock your poor sister’s death was to him and how he has

grieved deeply for her, but of late that grief has turned to something less

healthy.

He has a

painting of your sister, a beautiful work, but for some reason Philip has

developed the notion that Sophia, the image of Sophia, moves. Why, I cannot fathom. They have a foolish maid who may have started

this nonsense, but ever since he has been obsessed to the point of lunacy. Your

presence is greatly desired by my friend who feels that you may be able to

somehow contact your sister. To the contrary, I feel that your presence might

settle him back into sanity, to hear another tell him this is all fantasy,

that his grief has overwhelmed him, that your sister, although greatly missed

by all who knew her, is gone.’

I sent a cursory note in response and packed a

meager bag, not wishing to stay for more than a couple of days under Philip

Archer’s roof. Poor Sophia. I missed her every single day and the grief I felt

was indeed overwhelming at times. What

that man felt was not grief. It was

guilt.

I arrived at 15 Wisteria Grove, Chelsea, on foot, not wishing

for, nor affording, the expense of a carriage from the station. The walk did not put me in a better mood, as the

approach to the house was too heavily reminiscent of that day almost a year

before when I had rushed to my sister’s side, but found all her beautiful life extinguished. A young maid let me in to the hall and I immediately

averted my eyes from the staircase.

‘You came.’

Philip Archer was motionless in a gloomy doorway and so I

did not see him to begin with. When he moved towards me I was

frankly amazed at the damage a year could do. He was wrapped in a smoking jacket

that had seen better days and his hair and beard were unkempt. I was too

surprised at his appearance to avoid his embrace, so my cheek was grazed by his

lips and the smell of brandy assaulted my senses.

I stepped back in disgust and for a moment he looked aware of how far he

had slipped. He brushed a hand over

himself to smooth the inconsequential creases and fiddle with cuffs.

‘As you see,’ I finally replied and he nodded

before beckoning me to follow, striding purposefully towards the stairs. The maid bobbed at my side, her fingers taking

my bag from me.

‘Glad you are here, M’am,’ she whispered, and I

nodded.

‘Where are you Olivia?’ the artist called, sounding

angry suddenly, his voice travelling down the stairs to the little maid and

me. She jumped and scurried away, up the

stairs. I followed. There on the landing he was waiting in front

of the painting. His breathing had

become rapid and he turned to the picture, closely studying it before turning

back to me as I approached.

‘Mr Archer? Philip?’ I asked, trying to keep my voice

gentle.

‘See now, here, look here. Closer!’ he barked at me

as I moved to view the painting, and tried to grab my arm but I easily shook

him off and he seemed to remember himself.

‘Yes, yes, the work. It is almost too painful to

see it because you caught her likeness so well.’

For a moment, the artist fluffed a little with

pride, and turned to view his work like he used to, the conceit of talent

angling him. Then he saw Sophia again, her arms wide and the pretense slipped,

like my poor sister’s feet on the stairs.

‘But do you see?

She has moved.’

I looked at the painting, then back at him in confusion.

‘I see nothing out of the ordinary, why do you

imagine the painting moves?’

‘It was Bessie saw her first. Bessie!’

The small maid was summoned and she appeared at her

master’s side swiftly.

‘Sir?’ Her voice was soft and I remembered her

quiet sobs when I had arrived a year ago.

‘Tell Olivia, tell her, tell Miss Davis everything

you told me. Tell her!’

Bessie paused, her lips forming words but none

arriving. Her eyes flicked to the side

repeatedly and she closed her mouth, her chin decisively dipped as if her story

was ordering itself for the consumption of others. Philip gave a roar of

impatience, but was drowned out by the bell at the front door clanging. Torn

between following her master’s instruction and the call of duty, Bessie hurried

out her story.

‘I was dusting, Miss, and said that I was sure the

mistress looked different, that was all.’

Philip dismissed her unpleasantly, his hand pushing

her away so that she wobbled at the top of the stairs. I moved forward sharply and caught her

forearm. She and I exchanged a look of

solidarity.

‘Answer the door, Bessie,’ I instructed softly,

releasing her arm and she nodded, grimly.

‘I’m glad you’ve come, Miss,’ she repeated.

The visitor was Dr Carstairs, or Albert as I was

instructed to call him. A jovial man

with red whiskers and a ready smile, he was Philip’s physician and had grown to

be his friend, mainly due, he confided, to a lack of others. I think this last

piece of information was meant to make me feel an appropriate sisterly warmth towards the

artist.

‘How long have you attended my brother?’ I asked as

we sipped tea in front of the parlour fire.

Albert cast a look over at the snoring form of Philip who had fallen

asleep in the far chair.

‘Since this wretched business began,’ he murmured,

then gestured at the sleeping man. ‘It is good to see him sleep. That's your influence.' I gustured to me with a smile of relief. 'That has been half the battle I fear, his

insomnia. That fuels the fire of his

imagination, and such idle words of a parlour maid can start wildfires in the

minds of men.’ He flapped his hand in dismissal, ‘No, no, I don’t blame poor

Bessie for all this, she can’t have known what she was starting. I’m sure she meant nothing by it.’ He cast down

his eyes, then added, ‘I was also the doctor who attended your sister a year

ago. It is when I met Philip, and why he called on me again.’

I nodded, letting the subject of my sister rest for

the moment.

‘And he claims the painting moves? That it starts in

one room and ends up in another?’ I asked and he gave a short laugh.

‘No, if only that were the case, that would be

easily explained. He could move it in his sleep or the maid could be up to

mischief. No,’ he repeated, the smile fading,

‘no, he claims, well-‘ He paused, suddenly looking self-conscious, ‘my

apologies, but he claims your sister moves.’

‘What? How

do you mean?’ I exclaimed and he gave a pained look.

‘You see, that is the madness of it. Philip claims that your sister, the figure of

the angel, she moves within the picture.’ He raised his hand as I began to

object. ‘I do not for a moment think this is so, obviously, and I have examined

the painting and it looks just the same each day.’

‘Well, of course it does!’ I exclaimed and he

nodded.

‘Indeed, but still, he is adamant and cannot be

dissuaded. It began as a fancy but lately, lately, it has grown to a mania. I

felt you might be able to reassure him, to bring him back to himself. The anniversary, you see…’

‘Yes, I see.’ I spoke sharply for which I was

sorry. ‘I shall do what I can,’ I added, my tone softening, and the doctor

nodded, a tentative smile on his lips.

‘I am grateful, he thinks highly of you.’ I doubted

that. I doubted he thought of me at all. ‘I met your sister once, before, well,

when she lived. Were you too on the

stage?’

I relaxed a little in the chair as the man leaned

forward with interest.

‘No, my sister was the actress, as was our mother,

which was how she met our father.’

‘Of course, I saw your father in Macbeth at the Lyceum, he was a powerful

actor.’ There was something of the enthused school-boy about Dr Carstairs as he

spoke. I nodded indulgently.

‘Some consider it his finest performance. It was

one of his last. The influenza took him

and our mother the year after.’ My voice trailed off and again our guest looked

embarrassed.

‘My condolences, a great loss,’ he hurried out. I

felt guilty for my folio of tragedies and attempted to alleviate his

discomfort.

‘I had no talent for the boards, I could not

remember the lines. My father set me to work with Edwin Gordon on sets. That man could

make you think a city lay stretched before your eyes, or the inner sanctums of

a baronial castle. I was fortunate to see the theatre from such an angle.’ I

ended with a smile and he looked relieved and genuinely interested. There was a

moment of silence as I sipped my tea and he looked over at his friend. When he

looked back at me, he gave a quiet chuckle of relief and self-congratulation.

‘I am glad you have come Miss Davis,’ he murmured,

‘I am so glad.’

The next morning, three days before the anniversary

of Sophia’s death, I awoke to the sound of ranting from outside my room.

Hurrying into my dressing gown, I did not stop to consider my appearance before

opening my bedroom door. In the narrow passage leading to the stairs, my

brother-in-law was electric with excitement. I knew where he would be even

before I saw him. Sheltering on the

stairs below, her face creased with concern, was Bessie, who did not dare to

come any closer.

‘Philip?’ I called softly and he turned, looking

delighted.

‘See now! See, come closer! See!’

He ran to my side and dragged me to the painting of

poor Sophia.

‘What is it I am meant to be seeing?’ I asked, and his fingers suddenly pressed the back of my head closer to the image. I felt strands of hair pluck from my scalp

under his grip.

‘She has moved, it is unmistakable!’ Look!’

‘Please release my head from your grasp, brother,’

I whispered coldly, all pity gone in the sting on my scalp. His hand retracted

with a jerk and suddenly was on my shoulder, as if to steady me. I stood back, brushing his touch away.

‘I see nothing different.’

My answer was partly fuelled by the soreness of

pulled hair, but his face was suddenly doubtful and he turned again to the

picture.

‘But her arms, look at her arms.’

‘Philip, please, let us go down stairs, let us eat

breakfast. It is too early for this.’ I raised my hands in defence as he moved sharply

towards me.

‘Olivia, please, please say you can see it.’ His

voice was plaintive, pitiful.

I bent forward, and made a show of studying the

painting.

‘My sister was so beautiful, you captured her

likeness exactly,’ I said softly, raising my face to look at him. He frowned, and I continued. ‘I find it hard

to look at this painting. Please understand…’

To his credit he looked ashamed and reached out a

conciliatory hand which I flinched from but then allowed him to place on my

arm.

‘Dearest sister, I quite understand. At least now I

know I am not going mad. She has moved!’

With that he moved past me and down the stairs, as

Bessie skittled away in front of him. After he had vanished below me I realised

I had been gripping the banister so tightly behind me, my fingers had cramped.

Two days before the anniversary of Sophia’s death,

and I was once more awoken by the sound of Philip’s voice. This time it was near, very near, invading my

dreams and dragging me into consciousness.

‘Look now, Olivia, now, look!’

I was plucked from my bed by strong, manic hands

and, in my nightdress, I was hustled to the top of the stairs. I gurgled complaint that turned fearful as my

hand slipped on the banister, but he hauled me to the painting and waited for

my comment like an excited child. His hand was hot and tight on my arm.

‘You cannot behave like this, Philip, it is

madness!’

I tried to pull away and he looked crestfallen but

still maintained a grip upon me.

‘Please, Olivia, the painting.’ He pointed to the

angel with a shaking finger. ‘Tell me you see no difference.’

‘You have pulled me from my bed, dragged me, undressed, to a painting of my poor

sister. How would she feel seeing you

this way? Seeing you treat me so?’

We were too near the top of the stairs. With my

free arm I was holding the banister but if he fell into me we would both follow

Sophia to the bitter end. There was a pause and his fingers slackened on my

upper arm, then released. He brushed past me and down the stairs, murmuring

apologies in a distracted, disturbed voice. I did not relax until he had

vanished into the dining room. In front of me the painting of my sister with

her golden wings was bathed in morning light coming from the windows on the

landing. She had drawn closer to the frame. She was smiling.

The day before the dreaded anniversary, I woke to a

house subdued by quiet. For a moment I

bathed in the luxury of my surroundings but then I remembered where I was and I

stiffened, waiting, listening. In the

peace of the early morning there was the softest of sounds. It was muffled sorrow, unhurried and gentle.

I rose, wrapped myself securely in my gown before steeling myself for what was

awaiting me. On the landing, Bessie was between my room and the crumpled

figure of Philip, seated on the top step.

Her hand was raised as if she had been approaching my door to summon me

but had been stayed by the huddled form of her master. Caught between pity and panic she had frozen

in indecision. I nodded to her, releasing her from her task. She gave me a

brief bob, but her face was grim.

‘This is not right, Miss,’ she whispered. 'This is too much to bear.'

‘That will be all, Bessie, continue with your

duties.’

She left, her expression grim and as she passed

Philip I saw her hand hover over him for a moment before she continued by

without the comforting touch she obviously felt she should bestow. I approached

with less pity in my heart, but felt unequal to the task of handling the

man. I had been foolish to underestimate

his madness.

‘Philip, come now, what is this for? It will do no

good. Shall I call for Dr Carstairs?’

He raised his face, wet with tears, but he smiled

at me. Smiled. Broad and uncontrolled.

Silently, he raised his hand and gestured to the wall. I shook my head

with my eyes closed. I crossed my arms impatiently. He laughed, a horrible

noise and his finger shuddered insistently. I already knew what he was pointing

to and so looked at the canvas. Then I moved forward to his side, my jaw

lowering. The golden frame held a room, dark and undefined without any light to

illuminate it. I tore my gaze from the painting to my brother-in-law’s crazed

expression.

‘She’s gone,’ he whispered.

The day was shattered into pieces that tore at us.

Philip paced from room to room, seeking my sister who had fled her frame. I summoned Albert Carstairs and gestured to

my brother-in-law as he moved between rooms with a restless excitement. Albert

took my hands in his and made a comforting sound.

‘What is the matter, my old friend,’ he called to

Philip, who paused, smiling.

‘She is here, my angel has escaped her frame and is

waiting for me!’

‘Come now, Philip, come and sit with Miss Davis and

I and have some tonic. You will wear yourself out.’

‘I cannot, Carstairs, you do not understand. She is here, my angel, my Sophia, she is

here!’

I made a noise of distaste, of pain, at hearing my

sister’s name, and Albert’s face grew grim.

‘Come now, Philip, this has to stop. You are causing Miss Davis distress.’

Albert caught Philip’s arm as he passed. For a

moment Philip looked confused as to why he had stopped then seemed to notice

Albert’s presence, Albert’s restraining hand.

‘She has gone! Flown the painting and is here in

the house. Where is she? I must find her

before…’ he trailed off and looked at me fearfully. Albert shushed him, and he too looked to me,

a curious expression creeping over his features. He looked guilty. They both looked guilty. Then, as if drawn by the same thread, both

heads turned to look at the stairs. There was a moment of silence between us,

then Philip’s head jerked up to look at the ceiling and grabbed my arm.

‘She's at the top of the stairs,’ he whispered, absolutely terrified.

‘It’s Bessie, it’s obviously Bessie,’ I laughed,

despite myself. It was too dramatic, too melodramatic, and had spilled into

farce. Both men looked at me and Albert too relaxed into a smile at the three

of us clutching each other like children fearing the dark.

‘Philip, my dear Philip, only you could have us

cowering from your maid as she dusts!’

He gave a chuckle which spread to Philip, looking

between Albert and I with moment of clarity. He closed his eyes and placed his

hands over his face, laughing softly with relief and embarrassment. He only

opened his eyes again when he realised that Albert and I had stopped laughing

and he followed our gaze. In the doorway to the dining room,

wiping her hands on her apron was Bessie.

She had been in the kitchen washing dishes. Looking puzzled but smiling at our good humour, she

approached us, and with terrible accuracy she stopped at the foot of the

stairs. Philip crumpled into an unconscious heap between us.

He shook so hard his teeth chattered. We wrapped Philip

in blankets and placed him by the fire, as Albert and I spoke in hushed tones.

‘I refuse to believe anything is amiss in this

house beyond my friend’s piece of mind.’

Albert’s face was shaded in darkness as we sat away

from Philip, in the corner of the room.

‘What could disturb him so?’ I asked insistently,

my hand lightly resting on the doctor’s. ‘This is something other than

grief. This is mania.’

Albert leaned right back, vanishing into the

darkness, his hands withdrawing from me.

When he spoke, it came from the shadows.

‘I am loathed to speak, I know nothing of

certainties.’

‘I am frightened of what will face me when

I wake tomorrow morning,’ I exclaimed, and he suddenly leaned forward, his face concerned for

his friend. His lips formed a quietening

noise but I persisted. ‘Please, he believes my sister is roaming the

house. Why would that fill him with such

terror? I would be filled with joy at

such an impossible prospect.’

I waited for my answer. The kind doctor steepled

his fingers in front of his lips, his brow furrowed with deep, dark lines. When

he spoke after several minutes, it was halting and careful.

‘I arrived at this house a year ago to find chaos

and horror. Your sister,’ he paused,

looking apologetic, ‘your poor sister was at the foot of the stairs. She

tripped, they said, she tripped in the night and toppled. It was tragic, but

nothing-’ Again he paused, as he nodded to me in acknowledgement, ‘-nothing

else. But, Philip…’

He trailed off, his eyes lingering on the shivering

bundle by the fire.

‘Go on,’ I urged softly and his fingers rested on

my hand lightly. He turned back to me.

‘He was hiding from me, hiding away in the attic

rooms. He was drunk as a lord and

talking such nonsense.’

I sat up straight.

‘Nonsense?’ I repeated warily. He nodded, his eyes dipping, but then he met

my stare again with determination.

‘He was rambling wildly, but amongst it he seemed

to feel responsible for Sophia’s death.’ He waited to see if I would respond

but I was holding myself still. I nodded stiffly for him to continue. ‘I

thought he meant he had driven her to it. I told him to stop talking before he said

something that could not be taken back.’ His fingers pressed mine in

reassurance. ‘I didn’t want to hear she had thrown herself down those damn stairs

on purpose.’

I made a noise of shock and disbelief.

‘No!’ I snapped, withdrawing my hand, but he caught

my fingers again in his.

‘No,’ he agreed, ‘she did no such thing. Lord knows

I heard he had given her reason enough…’

He tailed off and I waited for more but he was

silent again.

Together, we led Philip up the stairs to his

room. His head jerked at the slightest

sound and he called my sister’s name in terrified tones until I snapped at him

to stop. As we passed the canvas he

whimpered and urged Albert to look, but darkness shrouded it. Albert looked to me and seemed to redouble

his efforts, heaving the muttering artist along the hall to his room. After Philip had been placed between the

sheets and swaddled in blankets, the doctor turned to me.

‘I can’t leave you here,’ he whispered and took my

hands. I raised my chin and forced a

brave smile.

‘Doctor, there is nothing here to harm me. There

are no ghosts in this house.’

‘It is not spirits I fear, rather my friend, my

friend who is very unwell. I could arrange for him to take a rest cure. I could arrange some treatment.' Just for a moment, the doctor looked desperate and I feared he would embrace me for want of something heroic to do. He shook his head sadly, adding, 'I can’t believe it has gone so far.’

We closed the bedroom door and the doctor squinted

into the darkness towards the painting.

It was lost in shadow. He turned

his gaze to my face, searching it as if to find his strength. I drew myself up

in an act of bravery.

‘Tomorrow is a sad day for us, for both of us. I lost my sister, he his wife. That awful

anniversary will arrive whether we like it or not, then it will pass. The fear

of the day is the spectre in this unhappy house.’

‘And the painting?’

I thought of my sister, my poor broken sister, at

the foot of the stairs, with her husband looking down at her, his hand still

raised.

‘It is just a painting,’ I replied, simply.

Dr Carstairs found me the next morning, sitting by

the fire in the same chair Philip had sheltered in the night before. I too was shaking and a glass of brandy was

cradled in my hand. He made his way

through the men clearing the hallway of the debris of the night: a broken cup,

a torn curtain, the body of my brother-in-law.

A sheet covered him as I could not bear to see his face, his stretched

mouth, his wide eyes.

‘What happened? Dear God, Miss Davis, Olivia, what

happened?’

I could not respond, exhausted by the effort of

remaining sane in the face of madness. He sank to the floor beside me, his hand

on mine, and he gazed into the fire with me.

‘He fell? Was it an accident?’

I wanted to nod, but instead I frowned.

‘Was it an accident when my sister fell?’ I asked

hoarsely. I needed to hear it from someone sane, someone outside this house. He looked as if I had wounded

him but he relented with the truth.

‘A year ago, in that morning of ranting he admitted

– or implied at least – he had been present, his hands had been on her. They

argued and he…’

I nodded, my eyes closing, relief flooding me and leaving me peaceful.

‘Last night,’ I whispered, ‘she did the same to

him.’

I remained in London until all had been settled. Our occupancy of the house, Bessie and mine,

was allowed by the landlord until all of Philip Archer’s effects could be sold

and his bills settled. Albert excused himself from my presence and did not return, his own guilt a barrier to our further communication. I counted his loss as part and parcel of Sophia's return and for a moment felt a twinge of regret, but that passed with the sales and the removals. When everything

had gone, all that remained was my meager bag I had arrived with almost a month

before, and a trunk of things that by necessity or desire would return home

with me.

Elizabeth Hemshaw, poor Bessie, faced me in her

coat and hat, her bag clutched in front of her.

I offered the cheque to her and she took it, concealing it away,

fighting a look of guilt. When she

looked at me again, it was with sad finality.

'I have so much to thank you for.' I offered, inadequately.

She gave a stiff nod and I hoped that it was not guilt I saw in her eyes.

‘Goodbye Miss Davis.’

‘Thank you Bessie, Miss Hemshaw. I hope the money

will help you as you have helped me.’

She nodded stiffly, then turned and walked out of

my life. A carriage arrived and two

strong men lifted my trunk onto the back and strapped it in place. In it were my sister’s possessions, to be safely

cosseted in my little home back in Oxford, together with four paintings. The first was by my late brother in law of my

sister, a beautiful angel in a darkened room.

The other three were

by me:

In the first painting, the angel had raised her arms.

In the second, she had approached the front of the

frame.

The third, the room was empty.